by JANET McKENZIE

Andrew Marr is the former BBC political editor, a distinguished journalist and writer, but he considers his daily art practice to be a central part of his life and the way in which he expresses himself most deeply. In two recent books on painting and drawing,1 he asserts the unfashionable view that a painting is, above all, an object with a subject, a form of communication, a narrative or message that cannot be expressed in words. He says: “During the second half of the 20th century and into the current one we have lived through an art period which often insists that the art object should be considered in and of itself.

“To ask, ‘what’s it about?’ has become a fundamental category error. But we can survive only for so long by thinking simply about the paint, the making, the pure gesture. Art history has always been the history of statements and stories. They have been religious and ritual stories, statements about industrialisation, or political statements, but for almost all that long time, art has been ‘about’ – and in no way independent of – the rest of the human story. My pictures, for better or worse, always have a subject.”

[image2]

Two exhibitions this spring organised by the Richard Demarco Foundation – the first, Andrew Marr: Highland River, at the Summerhall Arts Centre in Edinburgh, and the second, Art and Healing, at Scuola Grande di San Marco in Venice – revealed a dramatic shift in Marr’s work from perceptual drawing and traditional painting to intensely personal interpretations of the passage of time and the impact of Brexit. Marr has been a key figure in the intense and interminable Brexit conversation, and his paintings of Wester Ross in north-west Scotland and his small but dramatic drawn works made in Venice and Bogotá this month reveal the extraordinary transition made since a life-threatening stroke six years ago.

[image3]

As a television presenter, Marr’s appraisal and coverage of Brexit has been formidable. As an artist, he expresses a more private response to what he has observed, talking of: “the dislocation and distress of the political debate, spilling into mutually loathing tribes. What I feel inside is a kind of political sickness, a lack of balance (since I had a stroke six years ago, balance is a big issue with me), a feeling of angry disorientation – and I think that that is what these pictures are about. They describe a political fury, by no means limited to Britain, and one person’s distressed reaction to it.”

Studio International visited Andrew Marr in his studio in Primrose Hill, north-west London.

Janet McKenzie: The exhibition in Venice earlier this month presented your work in the context of the relationship between art and healing. It is interesting to see how the painting and drawing done since you had a severe stroke is a radical departure from the work you have done for most of your life. Can you explain what happened to you as an artist as a consequence of the stroke?

Andrew Marr: Absolutely. There is a dividing line before and after the stroke. Before the stroke, I was hurtling through life, doing far too much, not really thinking about who I was and what mattered, and the stroke was a mortal knock on the door, a wake-up call and it changed a lot of things about me, but for the point of view of this discussion it changed my painting. I had always drawn and painted from a young age. I can remember very early on looking at art books and being really excited about pictures and buying paint and being given paint. I would paint whatever was in front of me: the garden, my sisters, landscapes and also at school. It was suggested that I apply to Edinburgh College of Art, but I decided instead to read English at Cambridge. That seemed at the time to be the sensible thing to do, but ever since I have asked myself if I made a wrong choice at the beginning. As I developed my career as a journalist, a writer and broadcaster, painting became an activity for holidays and free weekends.

[image5]

JMcK: The early works of yours that are reproduced in A Short Book About Drawing are very capable, perceptual drawings, often made while travelling. By contrast, your most recent abstract drawings allude to a more internal life.

AM: My notion of drawing for years was representational and traditional; it was a discipline to apply oneself to, on a daily basis. It was particularly important to me when I was filming around the world and travelling a great deal. I found that the only way to lock something into my head was to observe it carefully and then to draw it. Afterwards, it was there for ever. So that was the kind of drawing practice I had. Painting, on the other hand, was reserved for holidays.

JMcK: Most artists would agree that drawing captures a moment and that it is the most immediate and subtle visualisation of ideas and experiences. Drawing can be both sensitive and specific not only in relation to the outside world, but in relation to ideas, sensations and memories experienced at the time of mark-making.

AM: I can go back to a drawing made 10 years ago and remember not only what it looked like, but where I was sitting, what it smelt like and what it was that I was feeling.

[image13]

JMcK: Can you remember what your first drawing was after your stroke?

AM: I drew a picture of the bottom of my bed, with my feet, in pencil. A great friend, Clive James, has been mortally ill for many years and he observes that the experience has given him a great subject. We all need a subject. After the drawings, when I came out of hospital, I could not walk properly and my left hand has completely gone, and I could only walk very small distances with a stick. On an emotional level – having to cope with not being able to run again, or walk long distances; cycling and swimming, too, were no longer possible – it was a time of giving everything up. It was clear I could not go outside and put an easel up by myself, with wind and rain and having to carry paints and brushes, but I thought, I can’t give up painting. I needed a safe space, where I could be in charge of the space around me: it’s called a studio. I’d never had one before. A good friend who lives around the corner from my home, the literary agent Xandra Bingley, said she had a spare room that I could use. I went there for the first year after the stroke, then I moved here. Once I was in the studio, I knew that I did not want to do traditional subjects and therefore I would have to make paintings from inside my head. I had always liked that kind of painting most.

[image8]

JMcK: Can you describe your life-changing episode?

AM: It was a strange, surreal experience. I was in hospital and people were sending messages and flowers, and Prince Andrew sent a big box of food. I remember thinking I was quite famous and very much the centre of attention! I was still preoccupied by how I was going to get to the loo, to manage day to day. Recovering from a stroke is jolly hard work with a lot of physio learning to walk again. There was not much time for reflection. I am more emotional than I used to be.

JMcK: Most of your new paintings are quite inscrutable. Are you conscious that you embed meaning, that you are constructing a symbolic narrative?

AM: I think if you overthink the processes, you are in trouble. Forms have to emerge and you are not always aware of what they mean. This painting on the easel was started today, and it started as an image of the Scottish Peace Garden (after a drawing of the same title) after my trip to Venice for the Healing and Art exhibition. Richard Demarco and I were talking about the Scottish landscape. The new painting has become a much darker Scottish landscape of Loch Lomond and I don’t understand aspects of it. I had a cancer scare last year and I made a painting that went to Liverpool for an exhibition about cancer at Nic Corke’s gallery. Its meaning was only clear to me afterwards. There is a painting on the floor next to the easel that is not finished, of me and my daughter in Venice. It’s a very emotional painting and quite crude.

[image4]

JMcK: It’s unfinished, but it’s not crude. The meaning implied in mark-making and the success of a work usually corresponds to whether the marks are heartfelt and whether the artist’s response is authentic.

AM: I was in the Ca’ d’Oro and there were muslin curtains that wafted in the breeze and there was a fleur-de-lis motif that I have chosen to use in the painting of the Grand Canal with architectural forms behind. Me hugging my daughter is an abstracted image: I’m very close to her and Venice is our place. I’ve been taking Emily to Venice since she was 12. We go to see the Veronese and the Tintorettos.

JMcK: Do you find physical travel and trying to capture it in some form to be a metaphor for spiritual travel, the journey of life?

AM: No, I don’t think so. When I was trying to draw the physical aspects of travel, I was just trying to create a record, a diary. In those days, I was drawing on my iPad. David Hockney persuaded me to use an iPad and I did and it is an amazing implement, with an infinite range of colour and brushes etc in one place, but in the end I did not like drawing on to a screen. It was always a very fast method of drawing.

[image7]

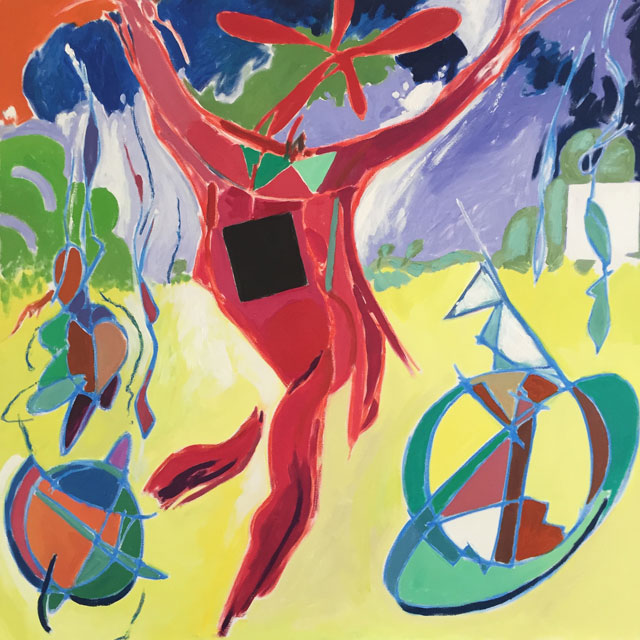

JMcK: Can you tell me about the Acrobat series?

AM: I had done the landscape works of Wester Ross that were on show in Edinburgh and they were specifically about the passing of time on a Scottish riverbed. Paintings and drawings, all one big project. There were no human figures, and I was missing that, so I sought the figure back in my work and I was drawn to one of the most traditional subjects of all: the clown, acrobats and jugglers. Picasso came to mind and Leger, Guardi (in Venice) and Tiepolo’s son. I wanted to distance myself from the Brexit debate, but, bit by bit, the clowns became bigger, more threatening, blundering, and they started to look as if they were breaking things, struggling unsuccessfully with gravity. I asked myself if this was a reference to what is going on in the political world at the moment. I am not making images that are anti-Brexit or pro-Brexit or anything like that. It’s about the division and the misery in the whole body politic. Everybody is angry and upset. Somehow, we’ve messed things up – that’s what the paintings are about, which is why I have called them the Brexit paintings.

JMcK: Does it feel dichotomous that you are in the powerful media position on certain days of the week and then quite marginal as many artists are for the rest of the week?

AM: I feel very marginal. I’m not deluded that I am an important artistic figure.

[image12]

JMcK: But you are playing an important role talking about aspects of it that people in the art world avoid.

AM: I’ve always been gabby, I like the sound of my own voice. One of the things is that, as somebody who paints and draws and takes it seriously, I have an obligation to explain what I am up to. I’ve never been satisfied by the approach of the art world that says, there’s the picture, you can’t say anything about it or ask questions about it, you cannot ask the artist what it is about – those are considered to be improper questions. ‘Just stand back and trust the artist and the gallerist.’ It’s not quite right.

JMcK: I would like to think that what you have done already in your books and what I am doing on the subject of healing and the visualisation of loss, and with others too, might come together so that art could be seen as part of the education system, not just for artistic merit, but for wellness and the betterment of society.

AM: I would like to make art feel a little bit less special: it should be something that everybody can do. The Victorians didn’t know that only a few people can be artists and geniuses so they taught everybody to paint and draw. Not everybody did it well, but they took it for granted – you learnt French, played the piano and you drew. It was part of the world. I think a bit of demystification is necessary.

JMcK: Can you explain the relationship between the sketchbooks and the paintings, both now and, say, 10 years ago, when your work was quite different?

AM: It’s completely different. I can draw things that relate to my emotional state. That is different from before. These images (Tumblers and Richard’s Biennale) are drawn from the Tiepolo paintings in Venice, and the attendants at the Ca’ Rezzonico museum were very annoyed with me for doing them. They did not want me there, or to be close up to the paintings.

[image6]

JMcK: The drawings in these, your most recent sketchbook, are beautiful works. I particularly admire these drawings and there is a wide range of mood and reference to experiential material, such as Tumblers (After Tiepolo), Richard’s Biennale and If I could write it.

AM: Drawing in a cathedral in Venice enables one to remember exactly where you sat on a certain afternoon. These drawings are the same and, when I look at them, they bring back the emotional tenor of the experience, in minute detail. In that sense, it is a diary.

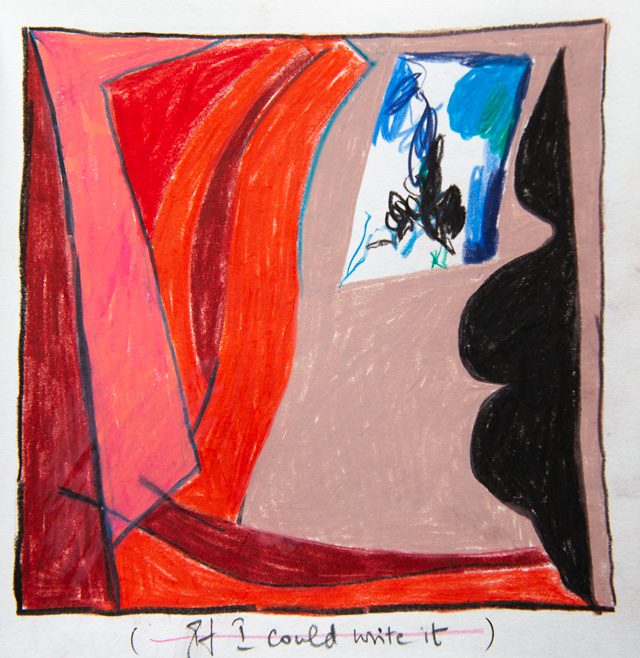

JMcK: Can you tell me about the visceral and oppressive drawing you have entitled, If I could write it? Surely, you don’t need to write if you can make a picture like this?

AM: It was done in Columbia and it conveys a slightly oppressive feeling. I was in Bogotá, which is 3,000 metres above sea level, and it was difficult to breathe, post-stroke lungs not working well, and the colours of Bogotá, lots of liver-reds and dark painting. There is a window there.

JMcK: So the title refers to wanting to describe the sensation that being in Bogotá precipitated. What is the Rough drawing in Venice about?

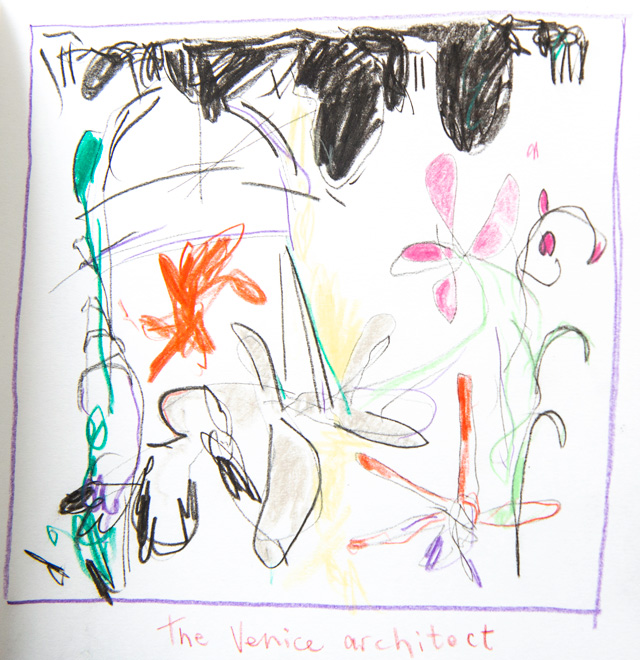

AM: Venice is all about backways and turnings that I have alluded to here. Venice is also quite a tough place to be, it’s not just gelato, there are savagery and ruthless commerce.

[image10]

JMcK: When you are making these abstract drawings (even though they have an external source) with features that might precipitate the mind working, do you sometimes think you are having a secret conversation?

AM: You start by letting your fingers go where they like. For a journey. When I stop is when I can see something representational emerging. I pull back and start again. The rest is about harmony and rhythm and balance, all those things we were taught early on. A curious thing, maybe for others as well, is that I find that if I draw a border within the edge of the paper, I draw much better.

JMcK: It asserts the picture plane and it gives you licence to operate within that space. Like a stage.

AM: I have found it a liberating action even though I did not know why I was doing it.

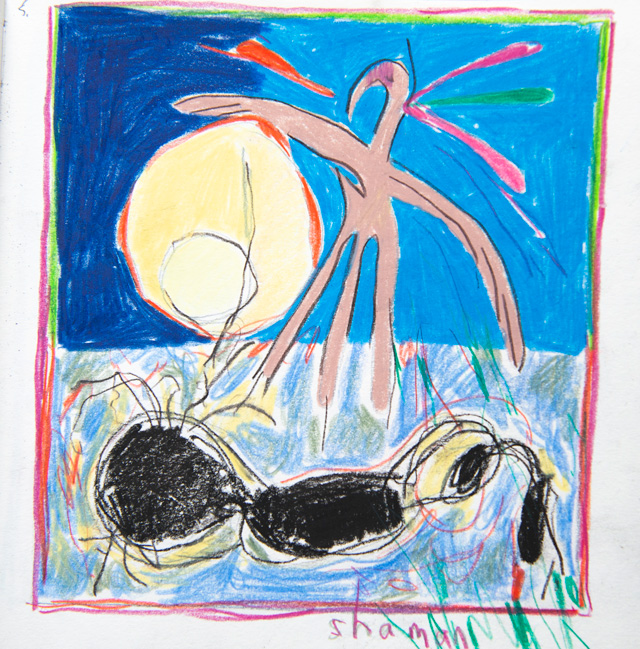

JMcK: It can be a theatrical device, giving freedom to operate within a metaphysical space. The Venice Architect is visual poetry and possibly my favourite drawing in this book. That naughty little scribble reminds me of Cy Twombly. It’s exceptionally lovely and then, suddenly, In Bogotá and Shaman are fierce and powerful. Good drawings are about authenticity.

AM: When a drawing goes wrong, it is often because you are trying too hard – you have to be in the zone …

JMcK: Venice, Emily has a sense of foreboding, and seems to refer to experiences beyond the immediate.

AM: I was sitting by the railway station in Venice, waiting for Emily, who had gone off shopping, and I was anxious. I thought of this as symbolic of the circus, but it is also just a formal element, a flourish. Sometimes, I go outside the border deliberately and others by chance. Thanks to Caran d’Ache, the colours are intense and beautiful. In Western Australia, I encountered sacred, profound Aboriginal art and was completely blown away. Every mark had a meaning, which I copied for hours in great detail .

[image9]

JMcK: Can you tell me about the sketchbook drawing called France Is Coming?

AM: I don’t know why I called it that, other than there is blue, white and red in it. In formal terms, I became interested in large dark blocks almost blocking out the picture space, and how you handle them. I just gave it the French title because it was made as Notre Dame was burning.

JMcK: It has been a massively tough and emotionally taxing time to be in the media.

AM: It certainly has, but it is also a great privilege. These drawings, Shaman and To Bogotá were made after a recent trip to Colombia, to the gold museum in Bogotá. The figure is an angry shaman figure – the conquistadors came in and took all the gold from the local Andean Muisca people. When they knew there was trouble coming – they took the king and killed him and surrounded him with all the golden objects and sunk the boat in a lake so the Spaniards never got near it. Relatively recently, when the lake was being dredged, the vast wreckage and gold were discovered. All the recovered gold is in the Bogotá museum; anywhere else, the gold was seized and melted down by the Spaniards and made into ingots and then transported back to Europe. It led to huge economic inflation and to the collapse of Spain. The moral of the story was a good one.

JMcK: Drawing has the capacity to process grief, redefine self, adapt to change or trauma. How has drawing helped you to return from a devastating medical episode?

AM: I draw every day. A day where I have not been able to settle down and concentrate on a drawing is a day that I do not feel so well.

Reference

1. Andrew Marr’s books A Short Book About Drawing (2013) and A Short Book About Painting (2017) are published by Quadrille.

-sketchbook,-2019.jpg)