by ALEXANDER GLOVER

It was April 2014, and Argentinian-born artist Amalia Ulman uploaded to her Instagram feed the first in a series of posts that marked a notable shift in her public persona. Over the course of the next few months, images of the 25-year-old’s new life in Los Angeles began to confuse her audience with tales of breast surgery, hotel bathroom selfies, escorting and drug-consumption. In September that year, Ulman announced that it had all been a performance piece entitled Excellences & Perfections (2014). The performance became known globally and brought with it a mixture of anger and adoration. Simon Baker, curator of photography and international art at Tate Modern, was one of those who adored it, and he included Ulman’s work in the Tate’s extremely popular exhibition Performing for the Camera, earlier this year.

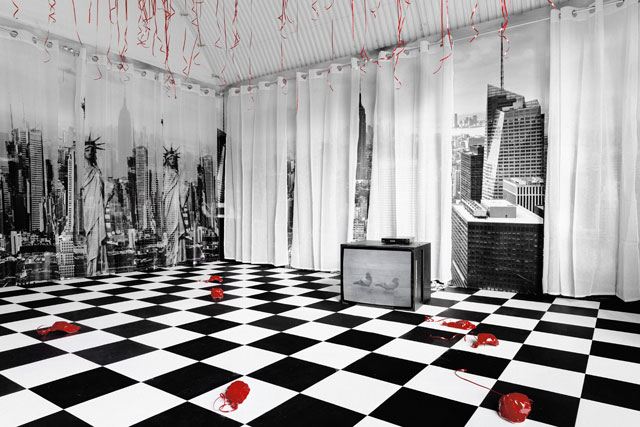

Ulman’s next performance, in February this year, commissioned by the 9th Berlin Biennale, saw the artist post a picture of a pregnancy test with the caption “BOOM haha”. The performance, entitled Privilege (2016), would go on to spark even more outrage. The artist’s new exhibition, Labour Dance at Arcadia Missa (London), continues the work of Privilege but within a new installation. We sat down to discuss the exhibition as well as the past two years that have led to the artist’s extraordinary rise.

Alexander Glover: Could we start by talking about the title of your new show, Labour Dance?

Amalia Ulman: It’s in relation to a show that I’m doing in Paris. Both are related to my previous performance called Privilege (2016). The thing that ties up the duration of the performance is pregnancy. It’s what gives it a beginning and an end. When I was researching things for the performance, I found all these videos of women dancing their babies out in order to make the labour process faster. It’s called labour dance and I thought it’d be a great name for a show in the UK right now [given the current UK political landscape]. I also found it very interesting because it was something that started directly because of YouTube.

AG: Did this not exist before YouTube?

AU: To be honest, yes. With a natural birth, you always have to move around doing stretches and squats. But I think it’s fairly new as, before, you would just go to the hospital, get an injection, become sedated, and push the baby out, etc. So it always existed, but now there’s a thing where you do #labourdance and upload your video.

AG: How has your view of pregnancy changed over the past year?

AU: With regard to that last performance [Privilege], everything came from my own personal experience and it’s definitely informed by my feelings in relation to that. With pregnancy, I was seriously considering going through it myself. Not now, but for the past two years. My situation was much more unstable in the sense of travelling around a lot and not really having enough money – to start a family, at least. So you know, things like that. I was also in an accident and I’ve been disabled since then. I get tired very easily and, you know, how would I be able to look after a kid at the moment? So, I guess it came from that, and from my roleplaying being pregnant. But I used the “baby bump” more as an object rather than anything to do with a baby.

AG: So you saw the baby bump [in Privilege] more as a separate entity than as an extension of your body?

AU: Yeah, I saw it definitely more as a “thing”. And the more I did the performance, the less interested I was in it. But it was part of the script, so I had to keep going. I find that, as the performances go on over time, they become less personal to me. But when that happens, it means I can focus on other things, like aesthetics and the overall picture. So it takes on a secondary level in that sense. So characters like Bob…

AG: Ah, who is this Bob, and what’s the story behind him?

AU: It’s basically what I wanted to do from the beginning of Privilege. I wanted to lay out a path to be more creative because I felt the language was/is too new to understand and might put people off. It was a conscious decision to use Bob as a means of coherent communication between the work and the audience. I want people to understand that there is a script, for example.

AG: Do you have a team that helps with the script?

AU: No, I do the whole thing myself. But it’s not all in stone. One of the things that was in stone was the pregnancy, because it created a necessary timeframe [nine months]. My art very much depends on audience involvement and how audience reactions change the works over time. It shapes itself in a way.

AG: Does it shape itself, or do you shape it in reaction to what you see?

AU: I guess both, actually. Something I couldn’t ignore, for example, was how people were reacting online to the US elections. The kind of language that is used throughout the campaign is definitely something that I incorporated into the performances. They [the performances] were supposed to end now, but will now end when the election ends. All this crazy behaviour just can’t be ignored. But going back to the performance … having a sidekick [Bob] is useful in the performance. Having characters, including an exaggerated version of myself, is what interests me at the moment.

AG: In Labour Dance, what was the symbolic purpose of having some balloons suspended in the air, and some deflated on the floor?

AU: I like working with really cheap materials. Like, really cheap materials. I think that comes from necessity rather than anything else. I’d rather make poetry with objects that have already been made and are surplus.

AG: Found objects?

AU: Well, I buy most of them, so not quite. I’m attracted to buying objects that are surplus rather than making something myself. It got to the point where I could definitely afford to produce everything myself. For example, I could definitely have made the American wallpaper in Labour Dance, but I just don’t see the point. It’s much better to use what’s around me. It’s also good because it’s easier to replicate, which is useful for exhibiting abroad.

With the balloons, I like how alive they are. Most of the objects I have used previously are in the room and don’t change. The balloons will change over time and it adds this sort of life/death dynamic to the show. A beginning, middle and end. It’s like a cheap trick; I like it when things are simple.

AG: You’ve got references to New York in this show, and the location for your previous work has often been in Los Angeles. What about America is drawing you in at the moment?

AU: Well, it’s not really about myself, per se, but more about mainstream depictions of how the world is. It wasn’t really about New York City, it’s just about cities in general.

AG: A lot of your performances for Excellences & Perfections (2014) took place in LA. Does what you have just said mean that those performances could have taken place in any major city? Or was there something about LA that allowed you to get into that role more?

AU: Not particularly. Some of the same performances took place in London, too. It was more about where the fashion worlds gravitated towards, I guess, for those previous performances. But what LA did help with, on a practical level, was that you could hide. You can go for months in LA without seeing anyone. When it comes to becoming someone else, it’s much easier because you’re not going to regularly bump into people you know in the street. I couldn’t have done the same in NYC. You have to make a huge effort if you want to socialise in LA. You have to plan in advance, so it’s very easy to hide away.

I did the third episode of the performance in my hometown (Asturias, Spain), with mixed materials from other places.

AG: Did you uncover anything when you went back to your hometown with these personas?

AU: Not really, as the only people I interacted with were my mother and my best friend and they’ve seen me making art since I was 16. So there was nothing really new going on when I went back. But they did help me with the work. One example would be when I needed a baby and they found one for me to take photos with for the performance.

AG: Some people got angry about that online. What was it about it that angered some people?

AU: I feel like it was mostly men who got upset about those first few performances. I don’t think they liked the feeling of, like, when you find out someone isn’t actually in love with you. It’s a similar kind of feeling, I think. People don’t like feeling stupid. It’s quite similar with the new performance. But you can easily find out that these performances are not real. I’m not trying to lie to people.

AG: What do you find more interesting: the people who were angered by your performances, or the people who go along with it?

AU: I was surprised by the anger. But I understand the reaction to the pregnancy, as it’s such a taboo subject. It feels like some sort of sacred topic that couldn’t be funny. It’s like Rosemary’s Baby!

AG: Bearing in mind that particular reaction, how did you react when you found out that you were going to be included in Performing for the Camera at Tate Modern earlier in the year?

AU: I was really happy, especially with how it was curated. For me, that was the best part. I have a personal connection to the Tate, more so than any other big international museum, because I studied and lived here in London. So it was very special. I enjoyed the curation because I was sick of being considered post-internet all the time and the things surrounding that. Yes, it’s a work on the internet, but it’s not just that. It’s a performance. I was really happy that they framed my work within a performance/photography context.

AG: Going back to your time in London, what kind of art were you drawn to while studying at Central Saint Martins?

AU: A lot of net art, which I still like, but I definitely went through an “Ugh, ‘I’m sick of this” phase. I never looked at, what they call, feminist art. I just make what comes naturally to me.

I’ve recently looked towards cinema a lot – Spalding Gray in particular. I love him so much.

AG: And with Excellences & Perfections (2014), were there any moments when the line between the role and reality got blurred? Or was it quite easy to compartmentalise?

AU: It was quite easy because I just made room during the week, two or three days, to devote to performing. Before I did that, yeah, it was confusing and quite messy. I couldn’t get anything done, doing it that way. But now I set aside specific time and days for performances, so it’s much easier.

I learn things from the performances that I wouldn’t have otherwise, and that’s how specifically it influences my life, I guess.

AG: We touched on it briefly earlier, but could you expand on what you have planned for your next show in Paris?

AU: This show in London is more about the female body – as represented by the balloons. Many women on online blogs have described their bodies as “deflated balloons” as a result of pregnancy.

The show in Paris is all about Bob (a pigeon). It’s about him being something disgusting that everyone hates. But he’s an art object, so he assumes a certain level of respect with some even finding him cute. So there are references to him in that sense, but there will also be bootleg material. For example, there are going to be a lot of fake shoes that I used in the performance. This is because at the very beginning [of the creative process for this show in Paris], I endorsed Gucci, for real. I was even paid for it. But then I bought a bunch of fake Gucci shoes from South Korea and made fake adverts with the fake shoes. I’ll be doing the same with Chanel because they saw what I did for Gucci and want the same thing. It’s kind of crazy.

AG: Really? Even though it’s publicly known that you used fake shoes previously?

AU: Yes!