National Portrait Gallery, London

15 October 2015 – 10 January 2016

by EMILY SPICER

Alberto Giacometti grew up in the Bregaglia Valley in Switzerland. By all accounts, he had an idyllic childhood. His mother was a strong, cheerful woman and his father was, in many ways, like Giacometti himself, a quiet, thoughtful man who knew he wanted to be an artist from a young age. While Giacometti senior lacked his son’s ambition and innovation, he managed to support his family in their modest home with the sales of his paintings. It is against the backdrop of these favourable beginnings that we are introduced to Alberto Giacometti in the National Portrait Gallery’s latest major exhibition, which is the first – it claims – to focus exclusively on Giacometti’s engagement with the human figure.

Giacometti remained close to his family until his death in 1966 at the age of 64, just two years after his mother died, aged 93. Throughout his life, he regularly used his indulgent family and girlfriends as models in his indomitable mission to capture what it meant, and what it felt like, to be in their presence, a goal that would have eluded even the most talented of artists. But Giacometti wasn’t just a talented artist; he was something close to a visionary.

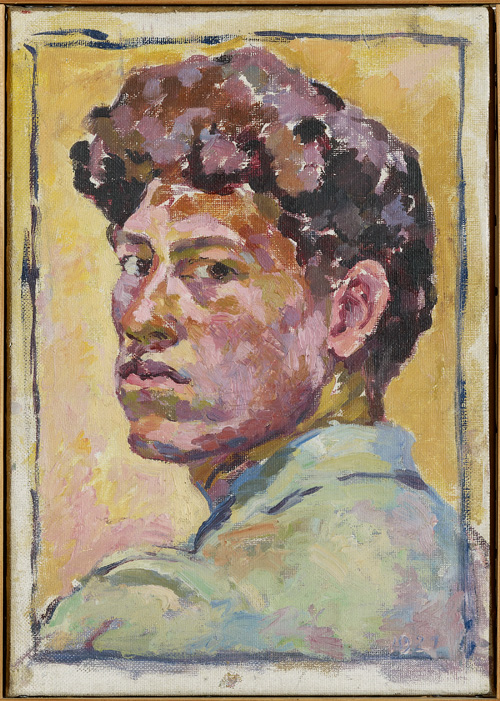

As a young man, Giacometti, while searching for his own voice, copied the colourful, post-impressionist style of his father. Egyptian reliefs provided inspiration for his sculpting, and, for a long while, the fledgling artist sought to “copy an exact appearance”, a goal that caused him a great deal of angst. It is something that any artist who has ever grasped at a “true” representation will understand. “The more I stared at the model”, he said, “the thicker the screen grew between myself and the real thing.” No matter how hard he tried to craft a likeness, his goal eluded him and eventually Giacometti “abandoned the real”.

In his endeavours, Giacometti was a very human painter. He was not one for pretence or pomposity, nor was he someone who claimed genius, although many say he was just that. No, Giacometti worked hard; he struggled. His efforts and anxieties are clear in the many versions of single images that line the walls of this exhibition. His early experiments in sculpture, in which he tries repeatedly, and with continuing frustration, to sculpt the head of his model, Isabel Nicholas, move from serene white plaster representations to small, rough heads, chiselled and hastily scribbled on in pencil.

A eureka moment came for Giacometti when he saw Nicholas from a distance one evening on the Boulevard Saint-Michel in Paris. The vision of a small figure surrounded by space had a huge impact on him and, for a while, figures only seemed to be “slightly real if they were minute”. So he made a lot of tiny forms, which he carried around in matchboxes. Scale and proportion had taken on a new significance and it was something that Giacometti would experiment with throughout the remainder of his life, in both painting and sculpture.

In order to overcome his compulsion to produce tiny figures, however, he started to make larger sculptures. These tall, bronze bodies, stretched and distorted like visions glimpsed through a desert mirage, look as if they have stepped straight from the most distant recesses of humanity’s past. They represent what it is to be human in the most universal and primal terms and all the contradictions that it brings, for nothing can be more paradoxical than the human condition. We are creatures of strength and fragility, resourcefulness and folly, gentleness and violence, and somehow Giacometti captures these complexities in the feverishly applied clay that formed the basis of his bronzes.

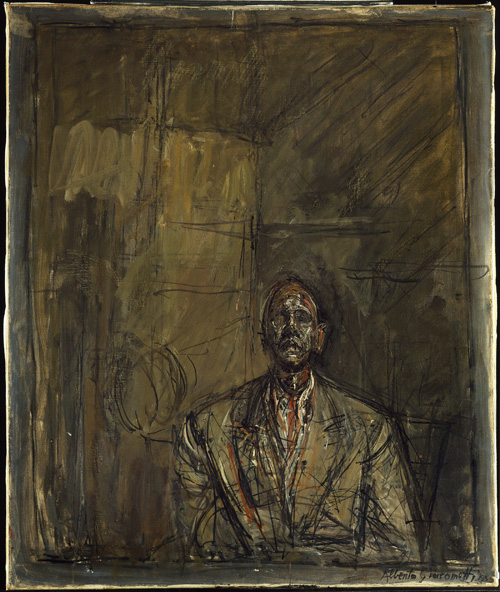

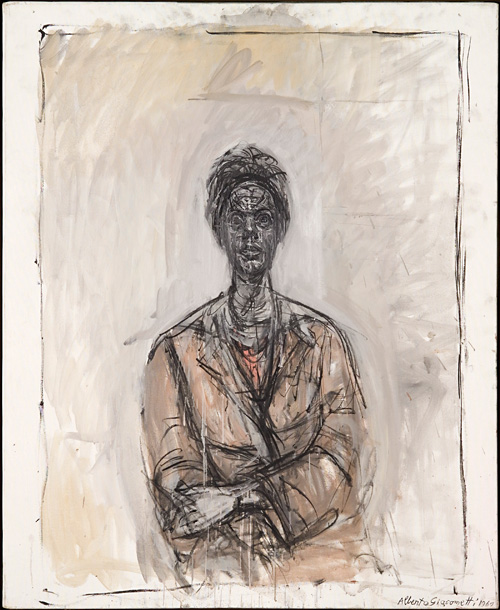

While Giacometti’s sculptures started to take on a monumental, totemic quality, his paintings continued to explore scale and space. Colour had long since drained from the faces on his canvases and outlines start to become less distinguishable. Figures sometimes merge with the background as if they are being consumed by their surroundings. They are there and yet not quite there – apparently in the process of either materialising or disappearing. The artist’s portraits of his mother, displayed in this exhibition in a single room for comparison, demonstrate Giacometti’s ability to represent the human condition on the one hand while also capturing the individual. Sometimes Annetta appears robust and solid, sometimes diminutive and fragile, almost engulfed by the cavernous space of the artist’s studio. But in every case it is impossible to ignore her presence, something that Jean-Paul Sartre commented on in his reading of Giacometti’s work as an expression of existentialism. It was Sartre, in fact, who referred to the artist’s endeavour to represent “pure presence”.

Some of Giacometti’s most powerful portraits were among his last. The final room in this exhibition is dedicated almost exclusively to paintings of Caroline from the 60s almost up to the time of the artist’s death. These paintings of a rebellious and wayward women wonderfully demonstrate how, even as an established and successful artist, Giacometti was still pursuing his aim to represent how it felt to sit before an individual, rather than capture their physical appearance. Giacometti was fascinated by Caroline. She was a wild child, who mixed with shady sorts. Her friends were engaged in nefarious activities in Paris’s underworld, and Caroline herself was no stranger to prison. In painting her multiple times, Giacometti captured the plurality of her personality and, in doing so, highlighted the shifting state of us all. After all, no one, not even the most constant among us, is unchanging. This is something that Giacometti seems to have been concerned with more than almost any other artist, and this is also something that he achieved in his portraits of this, his last great muse. Sometimes, Caroline looks beautiful and elegant; sometimes, vulnerable and awkward. In one portrait, painted in 1961, Caroline’s appearance is positively ghoulish. Her face is rendered skull-like with huge eye sockets, while a wash of shiny white paint adds a spectral feel to the image.

There are rooms in this exhibition dedicated to the important people in Giacometti’s life. One is full of portraits of his brother Diego, another of his wife, Annette. But this is a biographical exhibition and not hugely innovative in its conception. That said, it is well-designed and does render Giacometti’s personality as tangible as his heavy bronze figures. And, if one were trying to be clever about it, one might say that the “pure presence” is, in fact, that of Giacometti himself.