Installation view, Ai Weiwei: Making Sense, The Design Museum, London 2023. Photo: Ed Reeve.

The Design Museum, London

7 April – 30 July 2023

by VERONICA SIMPSON

Context, as the saying goes, is everything. An ordinary object can be transformed into something profound, dramatic, witty or disturbing through a shift in presentation and perspective, an escalation or shrinking of scale, or repetition – like the Chinese characters that spell out the names of 5,197 of the schoolchildren who died in the Sichuan earthquake in 2008, many as a result of the collapse of shoddily constructed schools.

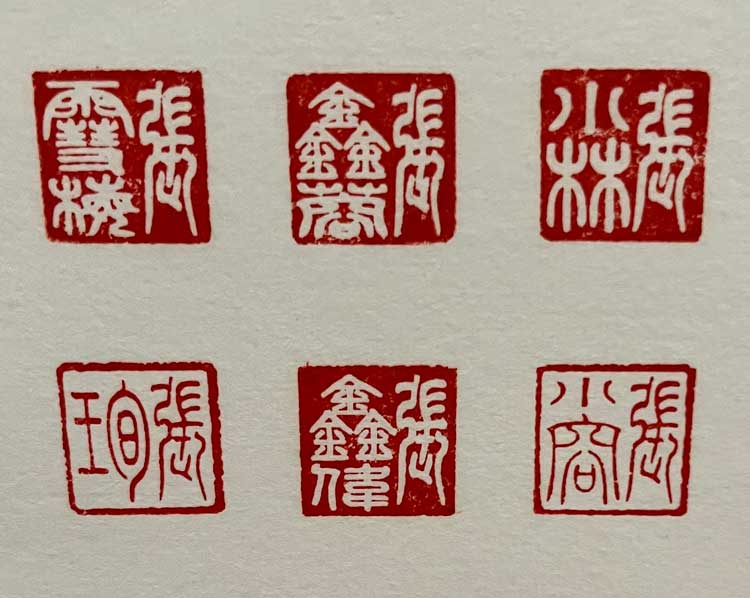

Ai Weiwei, Nian Nian Souvenir, 2021. Installation view, Ai Weiwei: Making Sense, The Design Museum, London 2023. Photo: Veronica Simpson.

In Nian Nian Souvenir (2021), Ai Weiwei renders this lost generation in ancient script, every name hand-carved into an individual jade seal, then stamped into its own little funerary box of red ink, on framed sheets of paper, in rows of 200 a frame, across 26 frames. Clustered together on a wall, these frames become a silent memorial, as well as an accusation: the grid-like arrangement reminiscent of second world war cemeteries, but also of the concrete structures of their schools, which were clearly not fit for purpose, an indictment of government neglect and corrupt construction practices.

Ai Weiwei, Nian Nian Souvenir, 2021 (detail). Installation view, Ai Weiwei: Making Sense, The Design Museum, London 2023. Photo: Veronica Simpson.

Ai has credited Marcel Duchamp with being one of his biggest influences, no doubt for his pioneering use of ready-made objects to make us question our values, but while Duchamp’s irreverent provocations changed the course of contemporary art, his interests were existential rather than overtly political. Ai, however, has long established his own genius for deploying pieces of everyday design as a form of excoriating rage and protest. Which is why the Design Museum is the perfect context for his first major UK retrospective since the Royal Academy show of 2015. He is an obsessive collector of items precious and ordinary, which he usually deploys for the purposes of holding the Chinese government to account for its treatment of buildings and people, and I was excited to see how he would use these items (as the press release says) as a “commentary on design and what it reveals about our changing values”.

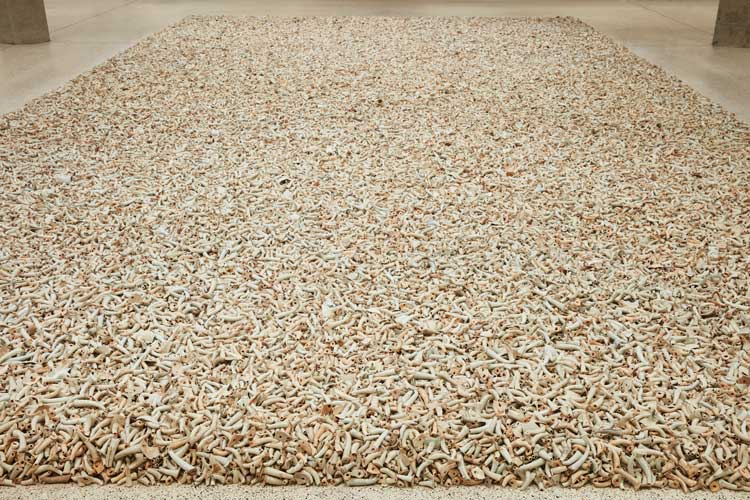

Ai Weiwei, Spouts, 2015. Installation view, Ai Weiwei: Making Sense, The Design Museum, London 2023. Photo: Ed Reeve.

We are promised “objects in vast quantities”, displayed in “expansive fields”. These are mostly spilled on to the floor in richly textured, but neatly defined, site-specific oblongs of 6 x 10 metres. Of the five “field” works, three strike me as particularly effective. Spouts (2015), as its name suggests, offers a multitude of spouts – 250,000, in fact - a bristling carpet of shiny, tiny, truncated porcelain spouts from teapots and wine ewers, allegedly hand-crafted during the Song dynasty (960–1279). Their massed presence here is thanks to the fact that any pot deemed less than perfect had its spout broken off. Ai wants this work to bear witness to the scale of porcelain production in that period, but also to act as a metaphor for the Chinese government’s relentless pursuit of conformity (ie, “perfect” behaviour) in its citizens – and the dire consequences for those who rebel, something Ai has experienced personally.

Ai Weiwei, Left Right Studio Material, 2018 (foreground). Installation view, Ai Weiwei: Making Sense, The Design Museum, London 2023. Photo: Ed Reeve.

Left Right Studio Material (2018) is a field work that bears witness to his experience at the sharp end of government disapproval. It comprises smashed blue vessels, all salvaged ceramic works from when Ai’s Left Right studio in Beijing was destroyed by the Chinese state in 2018. “A form of evidence,” as the press release says, “of the repression that Ai has suffered at the hands of the Chinese government, as well as … his ability to turn destruction into art.”

.jpg)

Ai Weiwei, Still Life, 1993-2000. Installation view, Ai Weiwei: Making Sense, The Design Museum, London 2023. Photo: Veronica Simpson.

Most compelling, to me, was Still Life (1993-2000), an orderly display of about 4,000 tools dating from the late stone age to more recent times, laid side by side in coherent groups. Axe heads, chisels, knives and spinning wheels bear witness to the analogue skills that got us through the first 4,000 years of human evolution. But what freaks me out is that my brain won’t compute that a layer of smartphone-sized, weirdly flat and oblong hand tools (perhaps used in scraping the fat or flesh from animal hides) has nothing to do with smartphones, so evocative are they of our ubiquitous contemporary weapons of mass destraction.

Ai Weiwei, Untitled (Porcelain Balls), 2022. Installation view, Ai Weiwei: Making Sense, The Design Museum, London 2023. Photo: Ed Reeve.

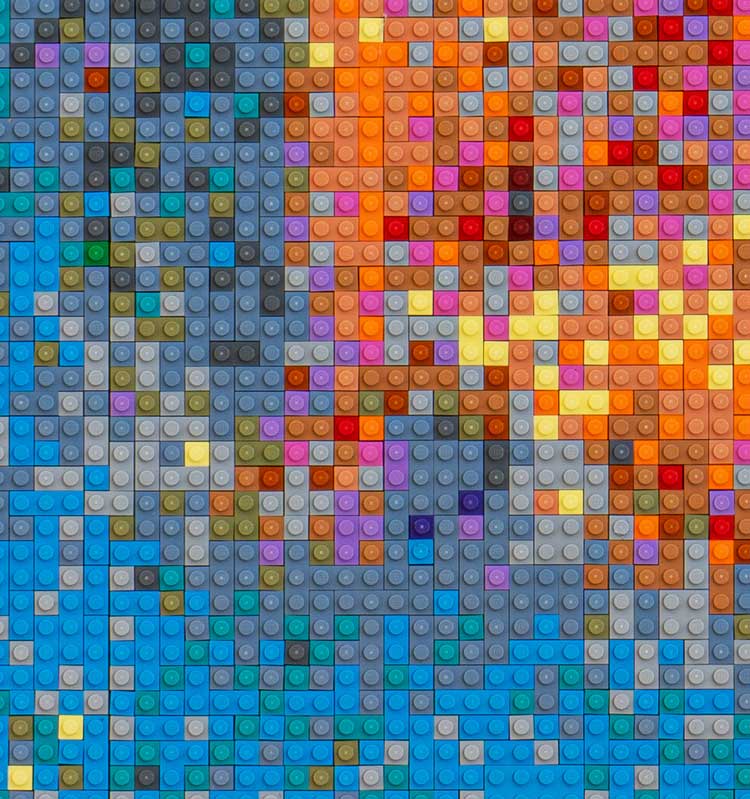

Another field, Untitled (Porcelain Balls) (2022), comprising thousands of tiny porcelain cannon balls, also from the Song dynasty, is baffling, both in the perfection of the tiny, round balls, and the fact that we instantly associate their material with fragile and decorative, high-status vessels. The idea of these hand-crafted spheres being used as projective pellets to kill or maim – as well as the sheer overwhelming mass of them – is almost too much to take in. The same is true of Untitled (Lego incident) (2015). A giant Lego spill, the enormity of its massed sprawl is somehow less impressive than the fact that, in 2014, when Ai started using the plastic bricks to make portraits of political prisoners, Lego briefly stopped selling to him. But thanks to his powerful following on social media, as soon as he announced this corporate censorship, the public donated bricks in their droves to demonstrate their support; these are the bricks now present in this artwork.

Ai Weiwei, Untitled (Lego incident), 2015 (detail). Installation view, Ai Weiwei: Making Sense, The Design Museum, London 2023. Photo: Ed Reeve.

Giant pieces of timber straddle this Lego work, but it is not immediately clear why. Then I discover that these are pieces of a dismantled ancient temple that Ai has collected, and the contrast of these venerable, hand-wrought elements from a devalued and disassembled place of worship with the tiny, machine-made, infinitely reproduced and reproducible pieces of Lego makes perfect sense.

Ai Weiwei, Water Lilies #1, 2022. Lego bricks. Photo © Ela Bialkowska/OKNO studio. © Image courtesy of the artist and Galleria Continua.

Sometimes, Ai’s fondness for spectacle and scaling up falls flat, as in the case of Water Lilies #1 (2022), a 15-metre-long wall work of tiny Lego pieces, which replicates Claude Monet’s Water Lilies (1914-26) triptych that hangs in the Museum of Modern Art, New York. The fact of its inspiration, or that it was made (and clearly not by Ai) from 650,000 identical studs of Lego bricks, in 22 colours, does not make it art; it is simply a rendering of a precious and beautiful artwork in tiny elements of no intrinsic value, in an arrangement that approaches the original’s subtlety and power only from a distance.

Ai Weiwei, Water Lilies #1, 2022 (detail). Lego bricks. Photo © Ela Bialkowska/OKNO studio. © Image courtesy of the artist and Galleria Continua.

The right-hand side of the work becomes clouded and darkens into what is meant to be a portal representing the underground bunker where Ai and his father, a famous dissident poet, were forced to live as exiles in the 1960s. We only know that, though, because we are told it in the captions in our leaflet. And it doesn’t render the work more profound or meaningful – not to me, anyway. Context – artist inserting traumatic biographical detail into copy of world-famous artwork that in no way relates to the event - isn’t everything.

To use another well-worn phrase, sometimes things get lost in translation. There are many ordinary objects that Ai wants to render profound through their transmutation into high-status materials, and mostly those presented here don’t work for me. I am not sure whether a loo roll becomes a significant object simply through being transformed into marble or glass, as happens here – even when one of them is blown up to a marble sculpture two metres in length - supposedly a reference to the Covid-19 pandemic and our dependence, at the time, on humble things.

Ai Weiwei, Marble Toilet Paper, 2020, Marble Takeout Box, 2015, and Glass Toilet Paper, 2022. Installation view, Ai Weiwei: Making Sense, The Design Museum, London 2023. Photo: Veronica Simpson.

A construction helmet rendered in glass is little more than ironic. I am underwhelmed, too, by his coat-hanger portraits of Duchamp. They don’t deliver the boldness of the Han dynasty urn on to which he painted a Coca-Cola logo, destroying the value of this precious, antique vessel but elevating our awareness of the power of US soft drinks branding. Thankfully, there is one of these here to remind us.

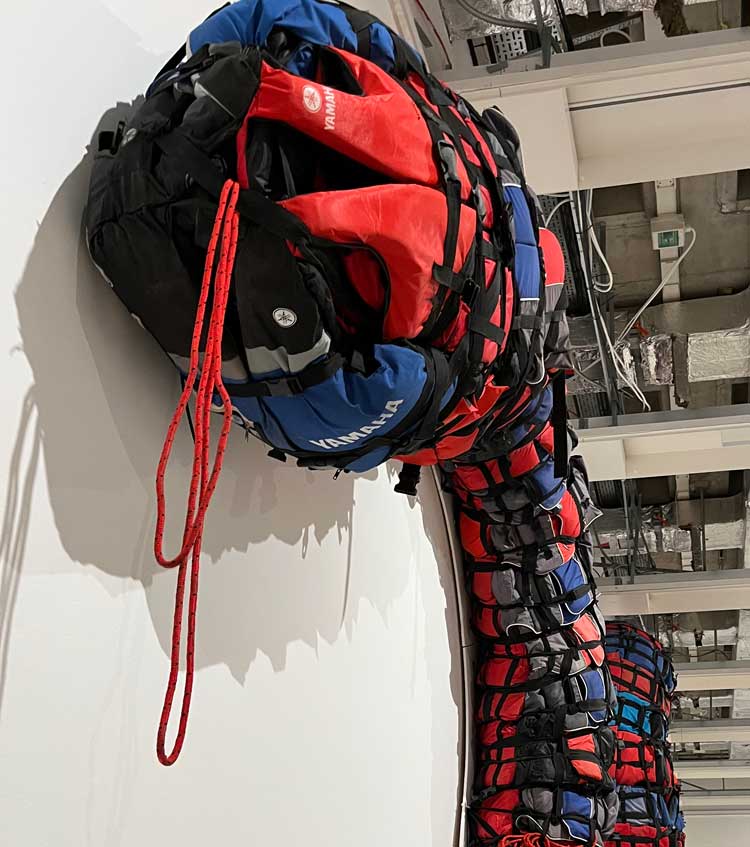

There is certainly traction and trauma in a sculpture made of life jackets, to commemorate drowning refugees (Life Vest Snake, 2019) though I’m not sure turning it into a snake, as Ai does here, adds anything. (And showing a corresponding Backpack Snake (2008), which doesn’t appear to relate to any human tragedy or atrocity at all somewhat diminishes the gesture.)

Ai Weiwei, Life Vest Snake, 2019. Installation view, Ai Weiwei: Making Sense, The Design Museum, London 2023. Photo: Veronica Simpson.

I first encountered a version of this Life Vest work on an exterior wall, arranged in more of a square formation and clustered on a building overlooking Copenhagen harbour. In all its affluence, cleanliness, observation of health and safety procedures and politely bobbing tourist boats, Copenhagen harbour offered a far more poignant setting.

The trouble with Ai’s work is that some of it has the heft of genius and some of it doesn’t but, because of his fame and undoubted talent, everything he does now takes on added significance. I don’t get what is so profound about the incorporation of Coloured House (2013), an enormous timber-framed house, into the Design Museum’s vast lobby – apart from the fact that Ai salvaged the frame of this house, which had belonged to a prosperous east Chinese family during the early Qing dynasty (1644-1911). Simply painting it in industrial colours, apparently to add a touch of something modern, doesn’t make it art and neither does perching the pillars of the house on large crystal balls, which are meant to add “status” to this “unlikely survivor”, as the press release tells us. These ingredients, in and of themselves, don’t add up to more than the sum of their parts. What Coloured House does achieve, judging by the response on my visit, is to give all the Design Museum’s Easter holiday visitors somewhere they clearly enjoy hanging out in the museum’s otherwise alienatingly cavernous atrium.

.jpg)

Ai Weiwei, Coloured House, 2013. Installation view, Ai Weiwei: Making Sense, The Design Museum, London 2023. Photo: Veronica Simpson.

One of Ai’s most enduring campaigns is to highlight the obliteration of China’s urban history and culture through the rapid demolition and “modernisation” of its cities (the show starts with his black-and-white photos of ancient cities, taken more than 20 years ago; no doubt none of the places shown remains). And I am with him there. We also see him bear witness to this cultural annihilation in a few video works shown here, the most disturbing of which is a film he made over 150 hours (several days) driving around Beijing in a minivan, touring its narrow backstreets, some dating back thousands of years, to capture them on the eve of their destruction. As I stand in the Design Museum watching just five minutes of this gentle and monotonous travelogue, I am aware that the commitment taken to its making and its presence here reinforces its message about the value of time itself as well as the things that have endured and evolved through the ages. All these streets are now gone, the caption informs us. In their place new roads have been built, and these also have their grim, filmic tribute, here. Their soundtrack of dull, multi-lane traffic hums continuously in the background.

-Middle-Finger-series-behind_EdReeve-2.jpg)

Ai Weiwei, Middle Finger series. Installation view, Ai Weiwei: Making Sense, The Design Museum, London 2023. Photo: Ed Reeve.

Ai is a consummate showman: his work wouldn’t have the power it does if he weren’t. That thought strikes me particularly after I have walked past the celebratory cluster of his Middle Finger photographs - world famous buildings foregrounded by his hand “flipping the bird” – a series that was begun long before he became such an iconic figure within the contemporary art world. Then I encounter those images all over again, framed or unframed, in print and poster form, ready to be snapped up by us, his admirers, for cash, as we exit through the gift shop. And you know what? Such is his allure, I bought one.

Ai Weiwei, Middle Finger series. Installation view, Ai Weiwei: Making Sense, The Design Museum, London 2023. Photo: Ed Reeve.