Edinburgh Printmakers

18 January – 22 March 2020

by CHRISTIANA SPENS

Photography and printmaking, although separate art forms with distinct histories and applications, have developed in parallel in many ways, given the invention and co-option of shared scientific and technological developments. One of these was the discovery of “actinism”’, the property of ultraviolet light and other radiant energy by which chemical changes are produced. While this led to the birth of photography itself, it also revolutionised the practice of print-making, enabling the development of techniques including photo-etching, cyanotype and photolithography.

[image11]

In this exhibition at Edinburgh Printmakers, a variety of emerging and established artists, mainly based in Scotland, show the innovative and interesting ways in which actinism continues to impact both art forms. Working with processes such as cyanotype, photo-etching and photolithography, these artists show the contemporary applications of this scientific discovery where photography and printmaking overlap and inform one another, revealing how entangled the forms are, and enabling conceptual explorations of memory, history, self and sense of place that use and contemplate these overlapping techniques.

[image8]

In Morwenna Kearsley’s F**k Weekends in the Country!, for instance, the Glasgow-based artist reflects on the thematic and technical history of photography by responding to the work of the American photographer Lee Miller, using photographic techniques inspired by Edward Weston. Her sleek and mesmerising images of bell jars in darkness also recall the stark, sublime poetry and prose of Sylvia Plath, inviting a striking, melancholic mood. This is typical of Kearsley’s art practice, in which she has previously developed ideas about how we are transformed by the images we consume. Here, with an awareness of Miller and Plath’s worth particularly, she allows the viewer to explore emotional depths articulated by these great American artists, whose subjects overlap, despite distinct forms. This experience of visual art, therefore, reveals this inter-textuality, or intervisuality, in which one viewer’s experience and inner thoughts are affected by a web of previous visual and semiotic ideas, and how this connectivity is implicitly integrated into the methods of photography and print-making, especially when combined and in dialogue with one another.

Also exploring and reflecting on process itself and its relation to everyday life, Marysia Lachowiz creates cyanotype and digital image constructions printed on to large sheets of muslin cloth that are suspended from the ceiling and drape down between levels of the building. These strikingly beautiful works are rooted in a methodology of mark-making as a way of connecting to one’s physical environment. Here, Lachowiz has drawn inspiration from her walks along the Fife coast creating impressions of that environment, reflecting on the power and destructiveness of the sea, and therein its sublime beauty, as well as the inherently transitory and changing character of the coast, as it breaks down and erodes over time.

These works emphasise the artist’s attachment to nature, and human connection to the natural world more widely – a theme that recurs throughout this exhibition as well as in the concurrent exhibition downstairs, Alexandra Haeseker’s The Botanist’s Daughter. As Lachowiz explains: “I’m interested in the marks people leave behind. My work is process driven and site specific. It is inspired by location, memory and the personal when that adds context and a wider understanding.” In these ways, Lachowiz’s works use a grounded methodology to explore what it means to have a personal relationship with nature, and why it matters – why such a relationship is an inherent, if often overlooked, part of being human.

[image6]

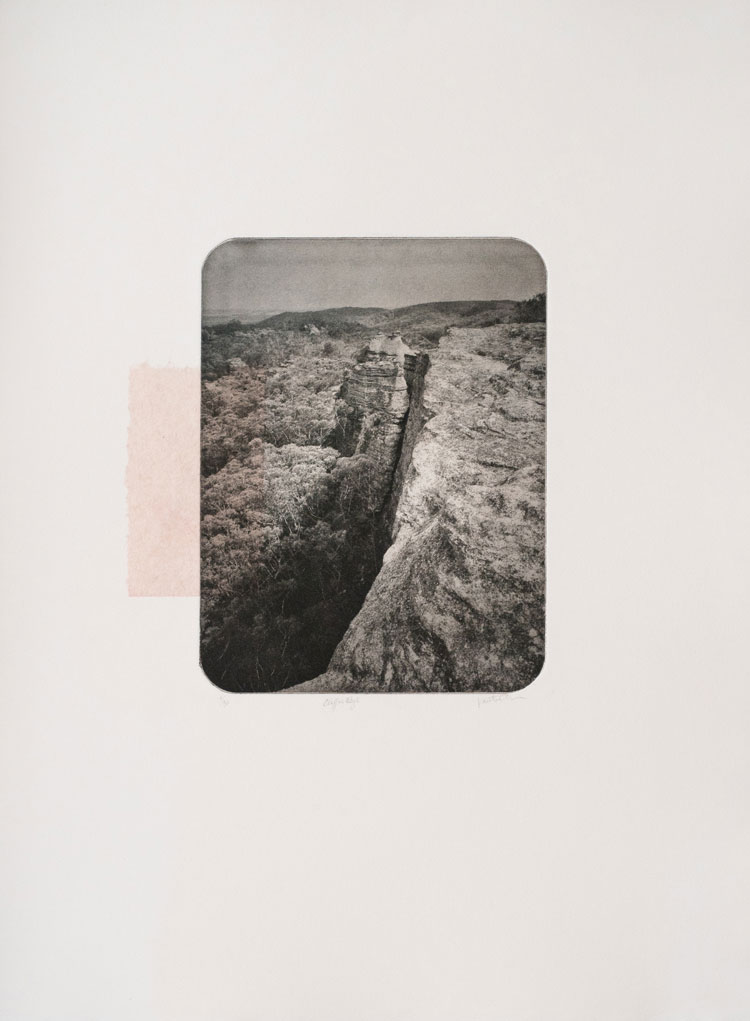

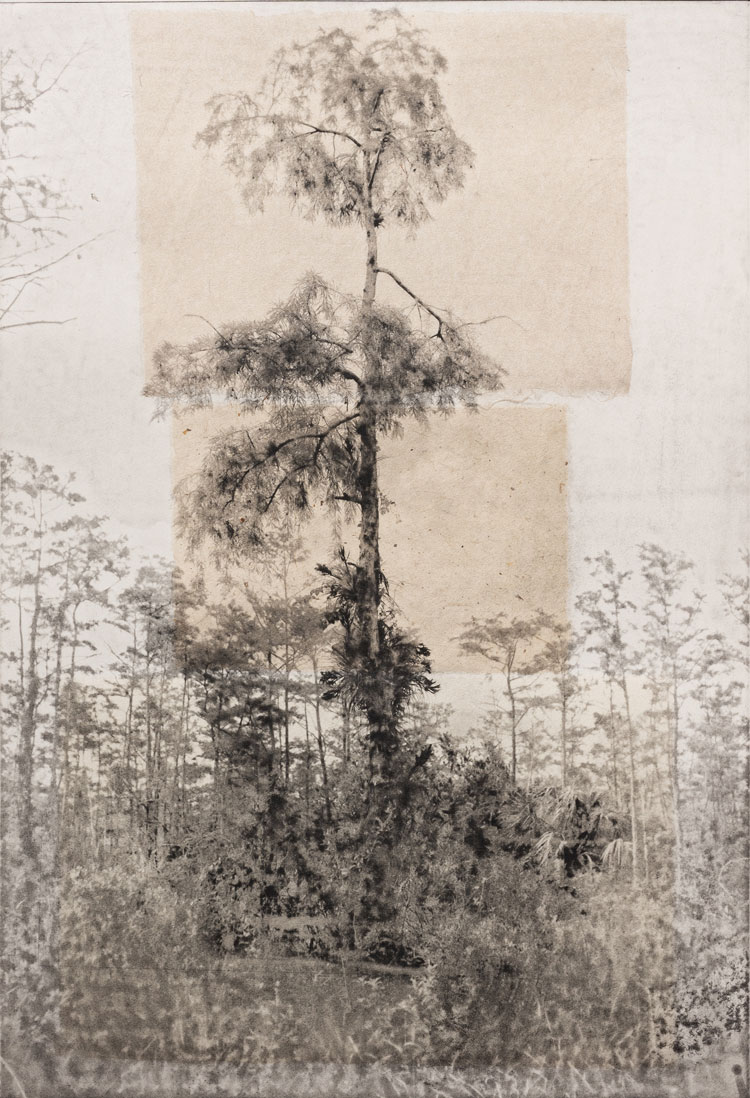

Kristina Chan, too, has worked individually and also in collaboration with Israeli-American artist Itamar Freed to explore the themes of human relationship with place, looking at subjective memory and the construction of images that question reality. In the black-and-white photographic series Survey, Chan shows grainy shots of rocks and cliff faces, and in her collaborative project with Free – Cyprus Trees – they have created beautifully intricate studies. In all these works, the fact that the image (and therefore its process) have been contrived to some degree is obvious, but that distance between reality and these representations imbues the images with a sense of the artists’ perspective and aesthetic presence in a way that is quietly mesmerising. In Dream in Blue, meanwhile, Chan and Freed have created a suite of images that depict a splintered and yet cohesive vision of natural beauty that is somehow haunted and unreal. Perhaps due to the striking blue from the cyanotype printing, or the way the overall image is broken up into 12 sections, there is a sense of time and memory being fragmented and confused. However, this complex vision seems as it should be – revealing the naturally splintered and ambiguous ways in which our memory works.

[image2]

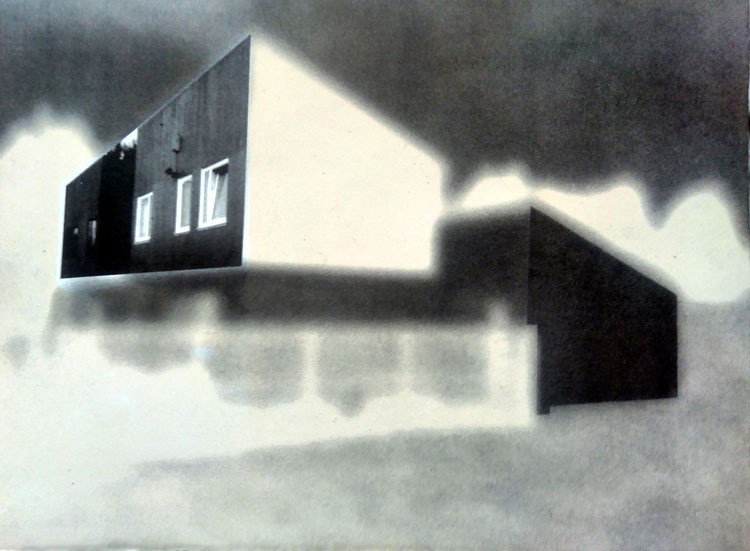

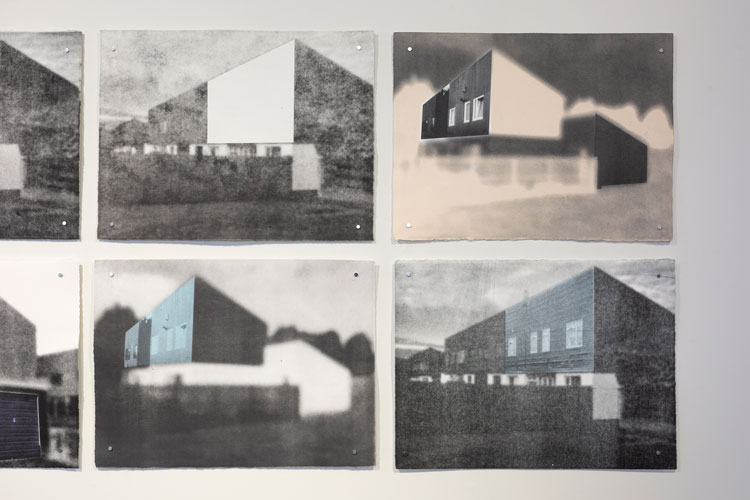

In Home, Nick Devison engages with the modernist legacies of the Livingston new town project. Fusing representations of brutalist buildings with his experiences of community and a sense of home there, he uses printmaking as a means to reveal the clashing sensations, memories and feelings that make up a subjective and communal experience of a place.

In all of these projects, then, in a cohesive and multilayered way, the artists show how mixed methods of photography and printmaking can uniquely and fascinatingly explore memory, place and human connection to environment. Moreover, they work together in such a natural and subtle manner, recalling the traditionally collaborative and communal nature of these art forms. Not only a sort of history of both forms, this exhibition is also a meditation on the possibilities of art to bring people closer to earth, through careful observation, grounded artistic process, and an awareness of the similar and entwined “process” of everyday life.

.jpg)