by JOE LLOYD

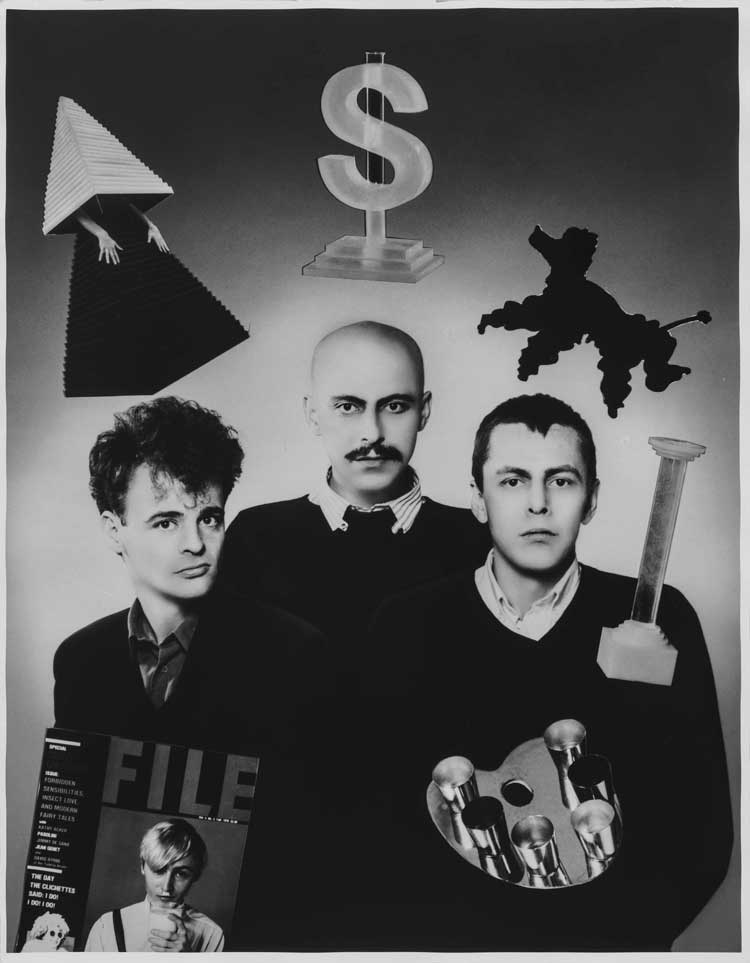

When General Idea burst out at the tail end of the 1960s, few knew what to make of them. A collective of three pseudonymous individuals – AA Bronson, Felix Partz and Jorge Zontal – who met in Toronto’s countercultural communes, they practised an art that seemed to defy all boundaries.

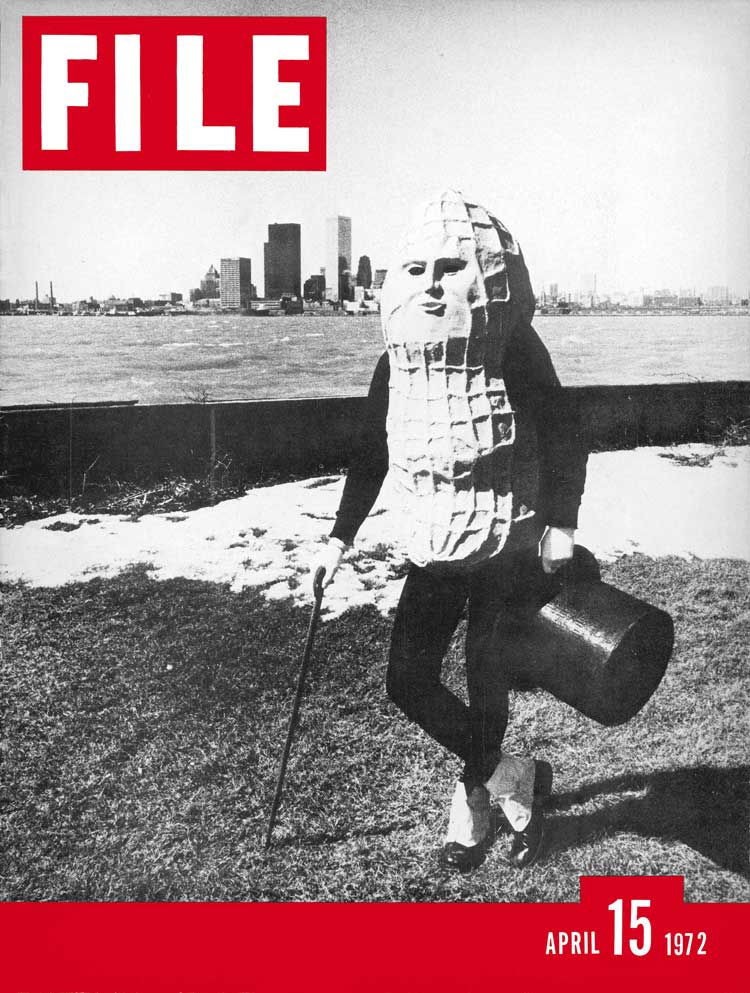

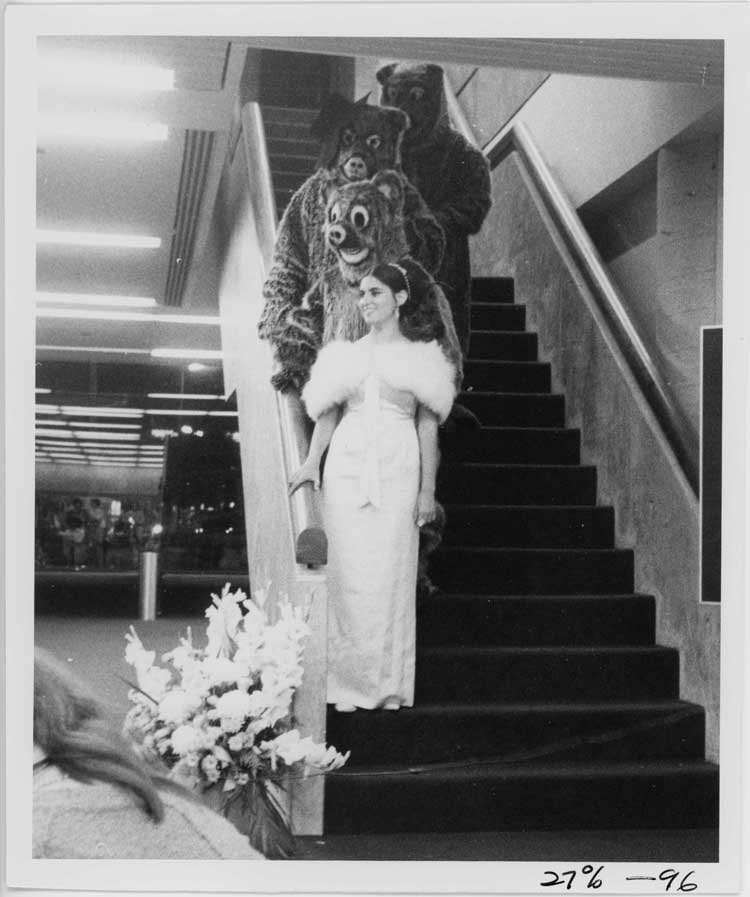

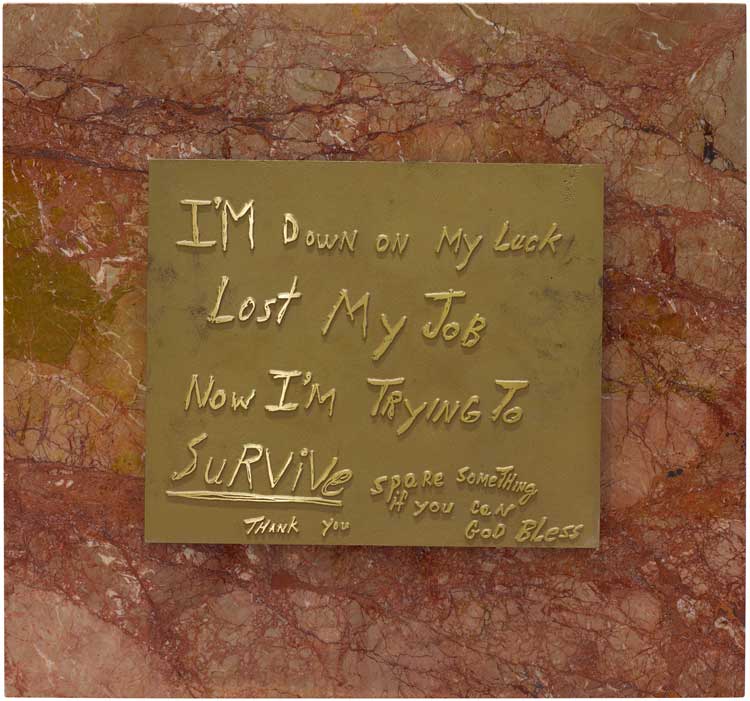

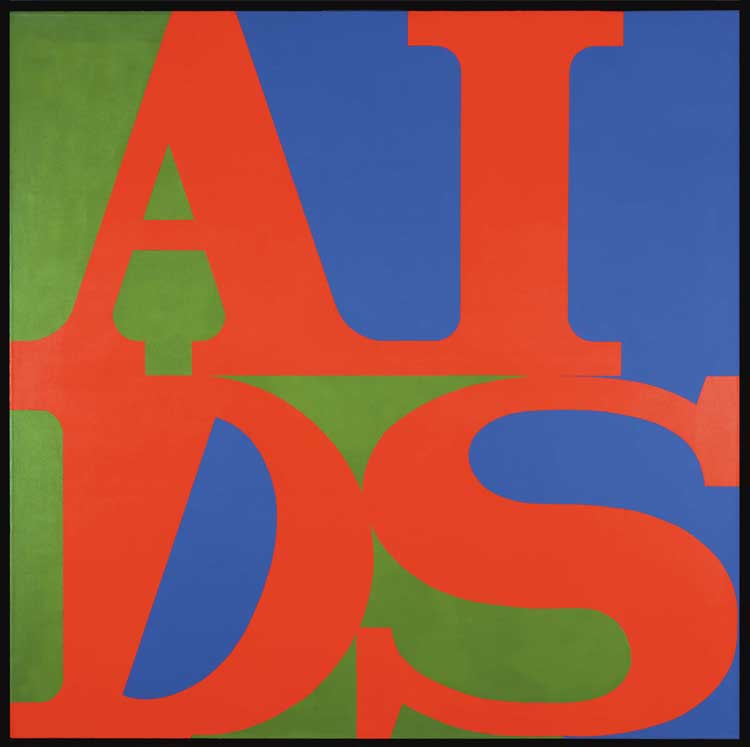

There were poster campaigns for mock ads, performance works that spanned days, a parodic beauty pageant, sculptures purporting to be ruins of a destroyed pavilion and vast mail art projects, including one piece that had correspondents tracking the date and time of their orgasms. They published a journal, FILE Megazine and found the alternative venue Art Metropole, still operating today. After a move to New York in the mid-80s, the collective turned its focus to the HIV pandemic, with a series of artworks that sought to make the disease visible.

[image2]

General Idea came to an end in 1994, after Partz and Zontal lost their lives to Aids-related illness. Bronson became a healer, training in therapeutic massage and practising professionally, to care for his friends. He returned to artist practice after a break, with powerful work that explored loss and recovery. He curated numerous exhibitions and worked collaboratively with many younger artists. He spent a decade as the director of the seminal art book publisher Printed Matter, Inc, and founded art book fairs in New York and Los Angeles.

Bronson had a productive pandemic. He has spent much of the last few years working on the largest retrospective to date of General Idea, at the National Gallery of Canada, and on a 750-page catalogue to accompany it. “Being 76 is kind of like being in lockdown,” he says. “You don’t leave your home as much. You’re not out partying at night, although I was a little bit. And your sex drive is a lot lower. So, to be in lockdown is so much easier if you’re older.”

Studio International caught up with Bronson after he had returned from the exhibition’s opening to his home in Berlin.

JOE LLOYD: General Idea has a retrospective at the National Gallery of Canada. How were you involved in the process?

AA BRONSON: Well, I’m the only artist who survives, so I’ve been intimately connected to the whole process for the last four years. In fact, it’s pretty much all I’ve done. The catalogue is finished. It’s 750 pages, it’s very big. I’m very, very happy with it. It’s beautiful.

There have been two other travelling retrospectives in the last 10 years or so. So, to tell the truth, I wasn’t so focused on the exhibition. But I was very focused on the catalogue because they had a good budget and I have a long history with artists’ books. General Idea started Art Metropole; in Toronto, we published a lot of books. And I ran Printed Matter for many years and started the New York Art Book Fair and the LA Art Book Fair. The book was obviously my territory, and they let me run with it. With the designer, we came up with a proposal for something that not only covered the exhibition, but the complete range of General Idea’s work, which includes performance, poster projects, things on the street, mail art projects right back when – really to cover the entire range of General Idea’s work and not just what can be represented in an exhibition. And that’s what we did, and they approved the project, and it moved ahead. I’m really, absolutely thrilled with it. It’s a book of a lifetime, to me. And at 76, it’s about time!

[image9]

JL: There are some aspects of General Idea’s work that strike me as difficult to exhibit or depict in a book, such as the mail art.

AAB: Yes, the mail art is not exhibited. Because, I mean, you can show some bits of paper in a vitrine, but it’s an activity that engages a whole group of people in exchange. And you can’t represent it by the debris that collects. But I hope that the catalogue itself has managed to capture some of that. Mail art is really difficult to exhibit. I started seeing mail art appearing in auction houses recently – and always for very, very low prices. I think it will always be low. Let’s see.

JL: How about performance?

AAB: For the section about performance, we ended up trying to capture, in a sense, memory of the performances more than the performances. In the book, that section is printed entirely on translucent paper in black and white, and so each image shows through the previous image. It’s a rather poetic section of the book, it’s not directly descriptive. In a way, that’s the most successful part. It’s the part that everybody oohs and ahhs over. But it’s not documentation in the normal way.

[image4]

JL: What first got you interested in printed materials as an artistic medium?

AAB: I don’t really know. My father was in the Canadian military, and we would move every three years. I was an extremely shy child. I ended up pilfering the libraries wherever we were and reading anything I could find that might remotely interest me. In a three-year period in one town, I could clean out the local library. And my bed would always have stacks of books around it – and I had no friends! That’s how it began in a way.

Then I studied architecture in the mid-60s, and it was the era of underground newspapers. With a group of friends, we dropped out of university, began a commune, and started an underground newspaper. And the thing about the underground newspapers that I think most people don’t realise is that they were very much a network. There was a kind of unspoken agreement that every underground newspaper would send a copy of every issue of its paper to every other underground paper that they could possibly track down. So, there were always masses of underground papers coming in the door and masses of them going out.

That’s how I came to be in touch with, for example, Situationist International because they were very involved with underground publishing in the 60s. And, especially in Europe, there were quite a few underground papers that were coming from art or arts communities, and not just from hippie communes.

I ended up moving to Toronto, where I worked as a designer at Coach House Press, which is a wonderful small independent press, at the time publishing mostly poetry, Allen Ginsberg and people like that. And it was associated with Rochdale College, at the time the world’s largest commune. The building was built to be a commune. It was 13 floors, and each floor was a different community. There was a coven on one floor, a black magic group on another floor, and people involved in architecture and ecology on another floor. It was an astonishing thing.

A theatre started out of it, Theatre Passe Muraille, where I ended up designing posters. And General Idea came out of that place. A group of us met there and became General Idea, and somehow between underground newspapers and designing books and posters for theatres, General Idea started to spill out ephemera for imaginary events. And it turned into artists’ books quite quickly.

We could find Yoko Ono’s Grapefruit (1964) in the local pharmacy, believe it or not, about 1969. So, there was a model there already. I think Fluxus was the first readily available model for artists’ books, other than you know the Russian constructivists.

[image5]

JL: Incredible! How did the network of communes and publications communicate across countries?

AAB: Because there was no internet, and the mail services worked fine but didn’t really give a feeling of connection, I feel that each group in each city felt in a way abandoned and disconnected and outside of the world. The only way to feel connected was to connect to people in other cities. It’s also a time in North America in which there was an enormous amount of hitchhiking, people just going to the highway and sticking out their thumb and travelling to the next city along in the network, the next city that had communes or underground papers or music festivals or whatever. So, it all comes out of the counterculture, I could put it that way. It doesn’t come out of the art scene so much as the counterculture. And I think you can see that, for example with Yoko Ono and John Lennon.

JL: Was there a point when you began to see the actions you were undertaking as art?

AAB: It was more like the people around us identified us as artists. We did a few theatrical events, something like a happening, in 1968 or 69. And we did a couple of what we thought were just inventive displays in the theatre lobby. Then an artist-run gallery invited us to be in a group exhibition, and we realised: “Oh, we’re artists.” Only one of us had gone to art school. But suddenly, we were artists. By early 1970, we already were thinking of ourselves as artists, and as what we did as art.

JL: I am sure you have been asked this a thousand times, but where did the name come from?

AAB: For the first exhibition, the one I just mentioned, we put in a proposal for a project, which we called General Idea. We didn’t have a group name. The gallery misunderstood and thought that General Idea was the name of the group. So, we thought, OK, good name.

[image6]

JL: When you began, your activities must have seemed very outre?

AAB: Yeah, I don’t really know what the art world thought! First of all, we were in Canada. The Canadian art world was mostly centred in Vancouver, which was many thousands of miles away, and to a lesser extent in Montreal. And the Toronto art world was pretty sad, frankly, pretty minimal. It was mainly painters, a generation older than us. There was Michael Snow – but at that point he was living in New York – and Joyce Wieland, both film-makers, but that was it. Toronto was just a terrible place for art. We didn’t really identify as being part of that art world, the more mainstream art world, and it just didn’t interest us at all. So, we didn’t participate in it.

When we began to work internationally, it came out of the mail art. For example, Robert Filliou invited us to be in an exhibition at the DAAD-Galerie here in Berlin, in 70 or 71. It’s extremely early. That was our first institutional show, and it was in Berlin, and we were in Toronto, and we had only just begun! We didn’t have any money and they didn’t have any money to bring us. That’s also when the Berlin Wall was very, very up, a difficult time in Berlin. When I look back on it, it’s amazing – our first institutional group show was at DAAD-Galerie Gallery a year after we started, and our first solo museum show was at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam in 79, 10 years after we started. It was another five before we had a show in a Canadian institution.

JL: When compiling the catalogue and exhibition, were there any works you had forgotten about?

AAB: To tell the truth, I don’t think so. I mean, there were works that other people had forgotten about, that I made sure got dredged to the surface because I didn’t want them to be completely forgotten. And the body of General Idea’s work is so wide ranging, it doesn’t lend itself to a concentrated form. We were lucky in this case with the exhibition, as the National Gallery of Canada has an immense, 16,000 sq ft [1,486 sq metre] temporary gallery. And they gave me a very free hand in proposing how we will use it. And the results are really amazing. I can pat myself on the back. I think it’s the best General Idea show ever. And I’m very, very happy with it. There’s a first room, which is a kind of an introduction to General Idea, with a few highlights. And then it goes into a chronological sequence, starting through the 70s, the 80s, and into the 90s. And going from, mail art, which is a very small kind of infrastructure through to very large installations at the end. It’s a very theatrical show.

JL: After General Idea came to an end, how did you approach transitioning to working as a solo artist?

AAB: I didn’t want it to be a continuation. I wanted to stop until I had something of my own to put out. So, I didn’t do anything for five years. Then I began to work again. I’ve worked collaboratively with a lot of younger artists, mostly. The exhibitions I’ve put on have mostly been highly collaborative, where I’m involved with a lot of people in the exhibitions, not just showing myself.

But at a certain point I realised that as the living memory of General Idea, there were so many decisions I was having to make about how a General Idea work gets installed, or how it gets represented in a catalogue, or how it gets talked about. In a way, I was functioning as if I was still General Idea. So, I began to produce some of the works that had been in the works, before Jorge and Felix died, which we had never completed. And I’ve now done quite a lot of that. I thought maybe I would feel guilty about it because it’s kind of like, making new General Idea works. But then I realised they were alive in our heads. And 100 years from now, nobody’s going to care who died first. It’s the work that will speak. I figure history can decide whether that was a good decision of mine or not, but I’ve put considerable time into producing some of the works that never manifested at the end of our time together.

[image7]

JL: The idea of working as a collective runs against the commercial art world’s idea of the individual genius.

AAB: Yes, that’s what the commercial art world wants. And I can’t help but wonder, would anybody buy General Idea if Jorge and Felix were still alive? Probably not.

It’s a peculiar thing. I feel there’s a big interest in collaboration among young artists and especially queer artists. There’s a huge interest in it and a big desire to participate in it. But also, as I get older, I find that I’ve become rather too much of a symbol of something. It’s hard for people to collaborate with me if they think they’re looking up to me. Once I turned 70, the collaborations started to die down. But during my 50s and 60s, I was able to do a lot.

The marketplace does not like collaboration. But I feel the museum world, the curatorial world and the critical world are all very interested in it. And I think especially young queer artists are very interested in how you can create a process by which to create art.

JL: Do you think an equivalent to the communes of the 60s and 70s could exist today?

AAB: It’s hard to know. There are still artists trying to do things with this structure, there are still people. But it was also at a time when most cities had a lot of unused space. Empty warehouses, old houses that had been standing abandoned. Now we’re at a time when in just about every city, space is at a premium, rents are high … I left New York nine years ago, but already young people were sharing apartments in a very crowded kind of way, but I’m not going to call it a commune. It was more like enforced sharing, just from economics. And I don’t feel the time is really here any more.

There is an artist from Los Angeles, Fritz Haeg, who purchased an abandoned rural commune with about 15 to 20 houses that had been designed and built by the people who lived there, and it was intended to be an agricultural commune. I think it lasted for about 20 years, but it eventually closed, and he purchased it. He’s made it into a kind of art project. It’s really fantastic. He’s made a very open structure, so anybody can go there and live there. I suspect they can stay as long as they want. But most people are probably liable to go for two weeks or four weeks or something like that. And they’re expected to kind of pitch in and help with the general bringing back together of the project as a whole. I think it’s rent free. It’s a fascinating project, because it’s kind of midway between architecture and art and something else.

JL: Now you have finished the catalogue, what do you plan to do next?

AAB: I’m a bit lost actually – postpartum depression? I’m not really sure what to do next. My dealers would like it if I would work and produce a catalogue raisonné of General Idea, which, if it happens, I think should be online. But I really don’t have the slightest idea. And sometimes that’s interesting: to start from a point of not knowing and see what comes.

• General Idea is at National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, until 20 November 2022.