Salzburger Kunstverein, Salzburg

25 February – 23 April 2017

by HARRIET THORPE

To gain a better understanding of painting today, Séamus Kealy, curator and director of Salzburger Kunstverein, examines the seminal text Cézanne’s Doubt, written in 1945 by philosopher and writer Maurice Merleau-Ponty, which explores Cezanne’s phenomenological approach to painting. Using the text as a backdrop to the exhibition, Kealy places together in one room the work of nine European artists who represent a range of styles within contemporary painting in order to assess how phenomenology is still central to modern painting, yet has developed formally as a visual reflection of its society.

Cézanne marked an important point for painters in art history: he disrupted the industry, if you like, forgoing formulaic rules that painters were previously enslaved to, such as formal representation and single-point perspective, in his quest to find a way of painting a “lived perspective” more accurate than that of painters before him.

In his printed essay text that accompanies the exhibition, entitled A Painter’s Doubt: Notes Towards an Exhibition, Kealy distils Merleau-Ponty’s stance: “This act of painting is more about sensing and experiencing objects and space, he argues, rather than simply reproducing them or mulling them over.”1

In different ways, the artists in the exhibition are all working with a phenomenological approach and, while we no longer expect painters to meet traditional values set out by art history, contemporary painters, by default, cannot avoid their place in the history of modern art.

Kealy adds another layer of examination by looking at the philosophies that were concurrent at the time of Cézanne. He relates Martin Heidegger’s “Dasein” and Franz Brentano’s “intentionality” to Cézanne’s parallel theories of trying to create a “lived perspective” through a phenomenological approach. As such, the exhibition is prefaced with the question: How does painting reflect its time?

Our contemporary world is full of images and we have a constant stream of visual stimulation available beyond our immediate surroundings. This is reflected in the source material chosen by artists in the exhibition. Swedish painter Anna Bjerger (b1973) paints from found photographs. Her work communicates the flatness and static order of a composed photograph – forms have a two-dimensional outline that doesn’t exist in nature, yet does exist in a photograph. In Off Piste (2016), a skier is frozen vertically ski-ing down a flat backdrop that was previously a mountain. She paints with oil paint on aluminium, which also reflects the glossiness of the surface of a photograph.

Cézanne’s paintings took on various perspectives at once, which often skewed the subject matter until it was altered into a physically impossible composition, yet Cézanne saw this as closer to how he was actually “seeing” his subject matter. While a photograph may be realistic in appearance, it takes only one fixed perspective.

Nowadays, from our city desks, suburban living rooms and other places where we passively absorb information from computers and phones, our world is represented in photographs through media and social media – as Kealy references in his essay text. Problems today result from people taking photographs at face value, believing a photograph as they would a fact, without understanding the context. Critic Will Gompertz, writes of Cézanne: “He realised around 130 years ago that seeing is not believing: it is to question.”2

We are in an era of reposting and reappropriation, which is also rife in contemporary art, with Richard Prince and Jeff Koons leading the pack. German artist Vivian Greven (b1985) paints directly from images of Bernini’s iconic 17th-century marble sculpture The Ecstasy of Mother Theresa – her smooth pearly face appears almost to effervesce in the three paintings in the exhibition. Through repetition, colour and a square canvas, Greven creates a modern icon, similarly to how Andy Warhol depicted his celebrity subjects. Mixing religious iconography with the language of contemporary celebrity speaks of our time. “Each representation of her appears equally as aloof to the next,” writes Kealy in his text. The other “figurative” painter in the exhibition is the Czech painter Daniel Pitin (b1977), who, inspired by theatre sets, films and architecture, works from his imagination, building scenes of abstract props with actors who perform on his canvas. Painting in dark earthy colours, he brings a melancholy to the scene with its conjured pathos. Like Greven’s, Pitin’s paintings resemble reality, yet do not represent it.

The categorisations of painting once seemed clear – history, portrait, landscape, still life – but since post-impressionism these seem less clear and less relevant, mostly because of phenomenology. Describing the works of another of the artists here, Titania Seidl (b1988, Austria), who approaches abstraction with a total grasp of depth and composition, Kealy writes: “All elements collapse together, albeit gently and without tension, into an ongoing state of becoming.” Instead of friction between genres, there is harmony. Kealy hangs Seidl’s three paintings inside a plywood pavilion in the centre of the large rectangular gallery, where they hold their own in the space – Seidl is a master of colour, composition and style.

Evolving like a graphic network of lines in space, the paintings of Kirsi Mikkola (b1959, Helsinki) evoke a contemporary experience unique to a post-internet time. The colours have been chosen from a digital palette – lime green, near fluorescent yellow, pink – and despite the strict angular shapes and forms, even constructivism feels far away. Kealy argues that the image could be seen as a Cartesian-like space. In a sense the work is fully phenomenological, a portrait of a graphic existence in a digital world.

Citing Bridget Riley as a reference, Dublin-born artist Mairead O’hEocha’s Tulips Reinagle (2016) shows a bunch of flowers that are almost psychedelic in their appearance, in the middle of the canvas on a light-grey-brushed background. There is an idealism, artificiality and naivety about them. Keeping phenomenology in mind, every artist’s impression of a bunch of flowers should be different and Gedrehte Becki Blumen (2017) by Gregor Hildebrandt (b1974, Germany) shows a blurry, digital pigment print on aluminium of a vase of flowers that references a 17th-century Dutch still life. Working with materials such as cassette tape, video tape, vinyl and acrylic paint, Hildebrandt questions what painting is.

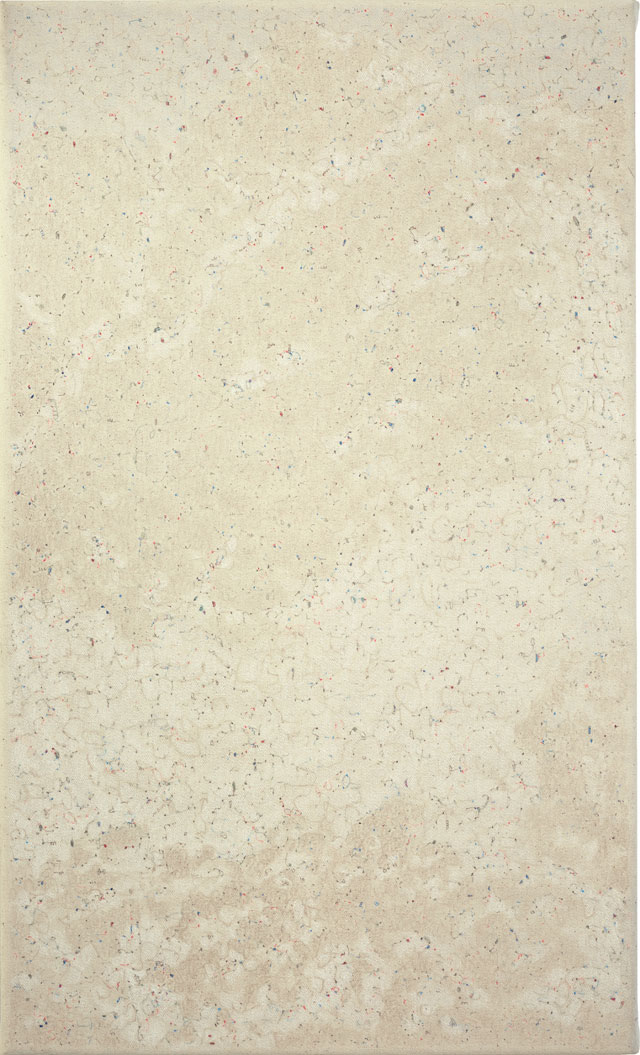

Echoing the texture of the plywood backdrop on which they are hung, the works of Carl Mannov’s (b1990, Copehagen) are the result of material experiments. Known to experiment with oil, charcoal and even concrete, Mannov treats the canvas like the piece of textile it is. Adjoining shapes of earthy colours, such maroon, brown and yellow, meet the boundaries of the shapes, echoing the batik technique of ink and wax. Flora Hauser (b1992, Vienna), who studied graphic design and media art, makes her own abstract language that, from a distance, looks like a dappled patina, yet on closer inspection pencil markings are revealed that define small shapes that are like letters or characters.

Each artist’s technique finds a different way to understand and communicate the world, no matter how it is pictorially displayed. Cézanne’s unrelenting attitude to searching for a methodology that would communicate this “lived perspective” is still relevant today. Kealy selects a quote by Merleau-Ponty that seems particularly apt for our current condition: “There is no end to this questioning, since the vision to which it is addressed is itself a question. All the inquiries we believed closed have been reopened.”

References

1. A Painter’s Doubt: Notes Towards an Exhibition by Séamus Kealy, Salzburger Kunstverein, exhibition catalogue, 2017.

3. What Are You Looking At? 150 Years of Modern Art in the Blink of an Eye by Will Gompertz, published by Penguin, 2012, page 81.