Bigger, Better, More: The Art of Viola Frey

Museum of Arts and Design, New York

26 January–30 May 2010

by CINDI Di MARZO

A 134-page full-colour paperback catalogue, available at the venue, provides insight into Frey's career from her childhood years on the Frey family grape farm in Lodi, California; first experiences with art in high school classes and at Stockton Community College (now San Joaquin Delta Community College); acceptance to the University of California at Berkeley and decision to attend the California College of Arts and Crafts (now California College of the Arts); graduate work at Tulane University in New Orleans; and years in New York prior to making the San Francisco Bay area her home base. Exhibit curator Davira S. Taragin, former director of exhibitions and programs at the Racine Art Museum, and Patterson Sims, former director of the Montclair Art Museum in New Jersey, interpret Frey's place within pivotal mid-20th century aesthetic movements and her role in ceramic art history. Susan Jefferies, former curator of modern and contemporary ceramics at the Gardiner Museum, adds a humanising touch that, no doubt, Frey could appreciate with personal recollections of the artist. Highly recommended to those intrigued by Frey's eccentric yet familiar vocabulary and flawless execution is an interview conducted for the Smithsonian Institution's Archives of American Art by Paul Karlstrom at Frey's studio in Oakland (27 February, 15 May and 19 June, 1995).2

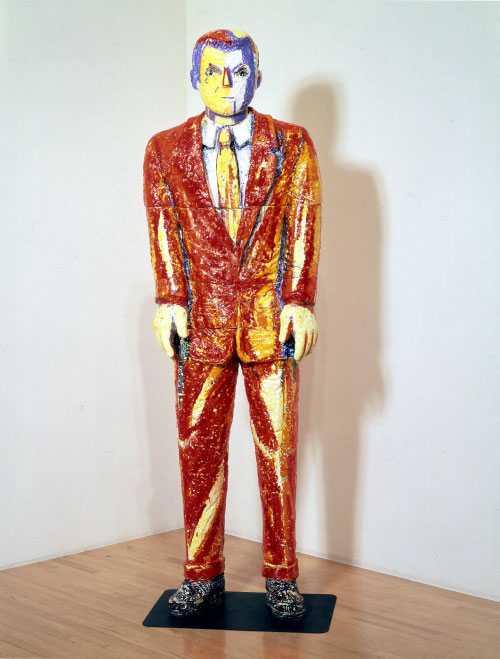

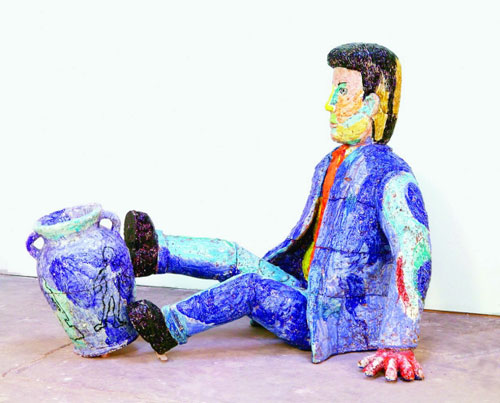

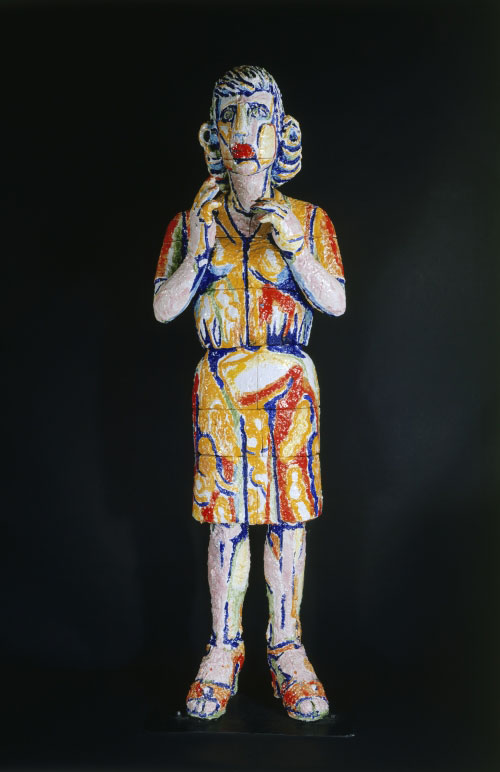

Just inside the entry to the museum's elegant, intensively modern facilities, Frey's 60" x 60" x 60" Western Civilization Fountain (1999) sits in the bustling lobby. Visitors will be directed to the second floor to view the exhibit. Although the sculptures, bricolage ceramics, plates and paintings cover a 35-year period, from 1969 to 2004, in all of their variety the works reveal Frey's determined career-spanning consistency. Certain themes, concerns and working methods persist; many traceable to Frey's early years. Born into a farming family with Huguenot roots, Frey recycled her childhood as easily as her found treasures. Historically craftspeople, Huguenots were skilled weavers, potters and metalsmiths. Frey witnessed women wielding great power within their households and men who, despite being heads of families, let their wives and daughters manage the fine details of daily life. Frey's paternal grandmother inspired many of Frey's female figures (eg Double Grandmothers with Black and White Dresses, 1982); Frey remembered that her maternal grandmother “spent her time with friends quilting”. This more decorative forebear might have been a precursor to Frey's large female figures clothed in dresses and hats (eg Lady in a Flowered Dress, 1983). Her father's mother “had much more power, and she spent her time being in charge of things”.3 The shifting nature of gender-based politics fascinated Frey. At the end of her life, she constructed a monumental ceramic sculpture, Man Balancing Urn (2004), reflecting her notion of male/female relationships. The work consists of a blue-suited man sprawled on the floor (the suit symbolic of worldly success) toppling a vessel (symbolic of art and woman's sphere). From his sad and ineffective gesture, facial expression and body language, we can assume the easy subversion of his power.

From her own accounts, Frey enjoyed defying and subverting convention. Like Joseph Cornell, she spent hours foraging for cast-offs in unlikely places. Frey found hers in flea markets and second-hand stores. Photographs of her homes and studios show her treasure trove arrayed in a baffling physical scheme, logical solely to its creator. Similarly, Frey's bricolage sculptures, plates and paintings resist narrative logic. Visitors will recognize imagery taken from common objects, but fail to glean any precise story or memory evoked by the artist. Making art from “junk” came naturally to Frey. In hindsight, she considered her father, a junk collector of prodigious scope, to be an early Funk artist. Like many Funk artists, farmer Frey became fascinated by the interplay of human activity and natural forces. In one of many such instances, the man who owned more than 500 old televisions and radios abandoned a farm vehicle in a field overgrown with weeds. In this case, nature claimed the day. This is not to say that Frey received encouragement to study art from him, her mother or brothers. Other than sharing a collecting obsession and his National Geographic magazines with his daughter, Reinhold Frey was a typical farmer. After high school, Frey left her family home for good. The effect of family on the artist can be inferred from the ceramic tableau Family Portrait (1995), where Frey appears as a sullen, red-lipped adolescent.

Beneath Frey's low-key personality stirred a passionate artist. Her career was a slow boil, perhaps because her male colleagues drew attention away from most other women artists, and because she divided her time among many pursuits: drawing, painting, sculpture and foraging for objects for her art and her personal collection. To contemporary audiences, Frey's work appears fresh and compellingly relevant to our times. MAD curator Lowery Stokes Sims comments that “besides issues of gender, I think the trajectory of Frey’s career may have been impacted by the fact that she was living and working in California and, often, she was associated solely with craft which would have disadvantaged her until the 1980s when multiculturalism opened up the art dialogue to other materials and genres. It is a testament to her work that it still has relevance today. As the catalogue notes, she was one of the first women artists to make their lives the subject of their art. Just a generation before, Frida Kahlo was important [to Frey] as a predecessor”.

Strong-willed and disciplined, Frey worked day jobs as a bookkeeper, a skill developed while helping her parents on the farm; in San Francisco (at Macy's) and New York (at the Museum of Modern Art). She gravitated towards art communities: the California College of Arts and Crafts (first as student, then instructor); Tulane University (where she studied colour with Mark Rothko); and Clay Art Center in Port Chester, New York (with Katherine Choy, a professor she met at Tulane's Newcomb College). In interviews, Frey credited her time in New York as critical with the often-quoted remark that in New York she had to survive to be an artist; in Calfornia, she had to be an artist to survive. If an artist wanted to be taken seriously in New York, he or she would have to make abstract work. Beyond gaining attention from writers, collectors and curators there, one had to surmount a formidable challenge: finding studio space. Both came far easier to male artists in the city. That male artists on both coasts overshadowed the few women pursuing painting and ceramics did not escape Frey, nor daunt her. She may have resented being described as influenced by peers Peter Voulkos, Robert Arneson, Howard Kottler and Manuel Neri and others working in the styles of the times: expressionist, figurative and Funk; with appropriated imagery; and exploring identity politics. Now, it is clear that Frey's work represents breakthroughs rather than echoes.4

More evident as directly influential, certain books and philosophies deeply affected Frey's understanding of her aims. Frey learned of the concept of bricolage, articulated by French philosopher and anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss (1908–2009), from writer/art dealer Garth Clark and Frey's long-time partner, artist/teacher Charles Fiske. In Lévi-Strauss's view, the remains of events or odds and ends of life can be reformed to more powerfully address new themes than labor-intensive craftwork. Voracious collector Frey was a sharp critic of “craft” or, rather, the low-esteem which craftwork received from fine artists. At the California College of Arts and Crafts, she wanted to work with clay but resisted a major in craft. She studied painting there with Richard Diebenkorn and, as mentioned, colour with Rothko at Tulane. Her sophisticated handling of paint and colour can been seen in expressionistic works like China Goddess Painting (acrylic, 1975). A primary characteristic, Frey's painterly approach to ceramics and sculpture admirably succeeds in Red Buddha plate (1994) and Weeping Woman (1990–91).

George Kubler's The Shape of Time (Yale University Press, 1962) and The Hidden Dimension by Edward T. Hall (Doubleday, 1966) became important to Frey's evolving vision. It is curious that, when she applied to the University of California at Berkeley, Frey aspired to a writing career. As a child, she devoured books borrowed from the public library and her father's copies of National Geographic.5 In her Smithsonian oral history interview, she recounted that when she went to Berkeley to register for classes, she realized that the stories she had to tell required a visual vocabulary and presence. Although at that point it struck her more as a feeling, later Frey understood that the images, memories and themes fueling her imagination demanded rendering in art.

Perhaps it seems contradictory, but Frey's facility across mediums fed a focused vision. Drawing, painting, ceramics and large figurative sculptures form a cohesive body of work in which the artist developed technical mastery while refining personal priorities into universal touchpoints. A full-time teaching post at the California College of Arts and Crafts freed Frey from her day job; a home in Oakland with ample backyard gave her space to create on an ambitious scale. In this setting, Frey's expanded her collection of flea market cast-offs and rarer objects. (Frey's tastes ran from low to high; she completed three art residencies at the Sèvres factory southeast of Paris.) Now somewhat stranded in the suburbs, Frey did not regret never having learned to drive. In interviews, she remarked that without a car, she didn't have to socialise, and people interested in her work had to knock on her door. As the years passed, more and more peers, students, collectors and curators visited. From the 1960s, increasingly Frey contributed works to solo shows and exhibitions in the US and overseas. She had active representation in the San Francisco Bay area with Rena Bransten, in New York with Nancy Hoffman, and with dealers networked through Bransten and Hoffman. When she died, she was an acknowledged master of ceramic art, honoured by a posthumous travelling retrospective and catalogue.6

Before leaving the museum, visitors should take the stairs (where more art from MAD's permanent collection is displayed) to the third floor to view the concurrent California Dreamers: Ceramic Artists from the MAD Collection with works by Frey, collaborations between her and Betty Woodman, and pieces by Arneson, Voulkos, Funk ceramicist David Gilhooly, Kinetic Ceramicist Clayton Bailey and other California-based artists. From Arneson's robust self-portraits and Voulkos's elemental vessels to Beatrice Wood's whimsical Father Hagerty and His Candy Bars and Peter Vandenberge's Dada-influenced Chilipepper Beans and Box, the diversity of these examples help to define Frey's achievements. The shy, retiring and fiercely independent artist, which viewers will have glimpsed on the second floor in the ceramic figure Double Self (1978), created dynamic, sometimes chaotic, always beautifully crafted and emotionally laden art. Beyond her unassuming exterior Frey remains “emphatically present”, to quote the catalogue.

Astutely gauging greater collector interest resulting from Bigger, Better, More, New York dealer Hoffman features the artist in her Chelsea gallery's first 2010 exhibit, Every Man, Every Woman: The Figures of Viola Frey (7 January–20 February).7 Some works in Hoffman's show demonstrate Frey's departure in her later years from painterly ceramic treatments. Unglazed white figures and large urn shapes indicate a late-career turn towards classical form. At the same time, Frey's series of bricolage groupings prove the tenacity of her hunger for period- and place-specific objects symbolic of society and culture. But there was, perhaps, another obsession which trumped collecting in Frey's consciousness: the human figure. Whether male (suited) or female (in fancy dress or unabashedly naked); portrayed in drawings, paintings or sculpture; or concealed among a cast-off hodgepodge on a bricolage ceramic, Frey's figures became her family, housed in her dream setting, a human museum without walls.8

References

1. Bigger, Better, More: The Art of Viola Frey opened at the Racine Art Museum (24 April–16 August 2009), travelled to the Gardiner Museum in Toronto (10 September 2009–10 January 2010), closes at the Museum of Arts and Design in New York on 30 May 2010, and makes its final appearance at the Arkansas Arts Center in Little Rock, Arkansas (13 August–28 November 2010).

2. See oral history, Smithsonian Institution's Archives of American Art: http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/oralhistories/transcripts/frey95.htm

3. Ibid

4. Voulkos moved further into a Japanese-inspired aesthetic which Frey entertained briefly earlier in her career; Arneson, whom Frey described as most influential of her peers, created personal works with specific content rather than the open dialogue characteristic of Frey's art; and Kottler began with commercially produced ceramic plates as the base for commercially produced or handmade decals while Frey incorporated or recreated found objects into her handmade ceramics.

5. Frey's large ceramic figure Mrs. National Geographic (1977–1978), a portrait of Mrs Gilbert H. Grosvenor, daughter of Alexander Graham Bell and wife of the magazine's founder, pays tribute this influence.

6. Viola Frey: A Lasting Legacy with essays by Kenneth R. Trapp and Ric Ambrose, published to accompany the self-titled exhibit held in 2005 at the Avampato Discovery Museum in Charleston, West Virginia, Louise Wells Cameron Art Museum in Wilmington, North Carolina, and Nancy Hoffman Gallery in New York City.

7. For more information on Hoffman's exhibit, go to: http://www.nancyhoffmangallery.com/

8. See exhibition catalogue, p.60.