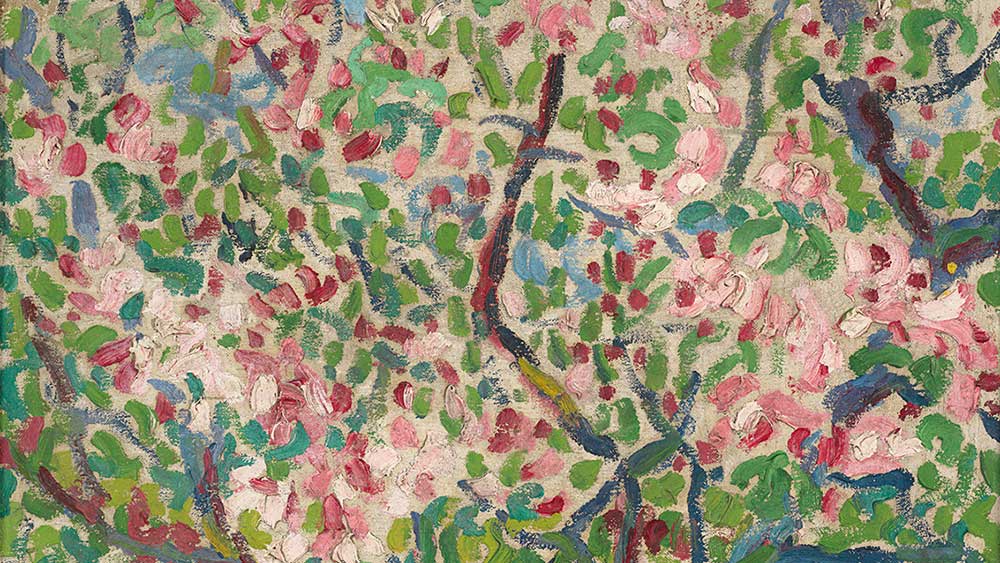

Erich Heckel, Blossoming Branches, 1905 (detail). Oil on canvas, Brücke-Museum.

Brücke-Museum, Berlin

24 February – 4 June 2023

by SABINE SCHERECK

The members of the artists’ group Brücke (meaning Bridge) joined forces for just eight years, from 1905 to 1913, yet they produced a groundbreaking body of work that was instrumental in establishing expressionism as an art movement. In 2018 and again in 2022, the Brücke-Museum in Berlin zoomed into the crucial years of the Brücke’s existence: its demise in 1913 and its pinnacle in 1910, respectively. This year, the museum unfolds the Brücke’s origins with its exhibition 1905: Fritz Bleyl and the Beginning of the Brücke – and brings, through almost 150 works, a rich and varied collection of paintings, drawings, watercolours and woodcuts into view. Moreover, it reminds us how progressive these young men were, not only in their art but also in how they marketed themselves.

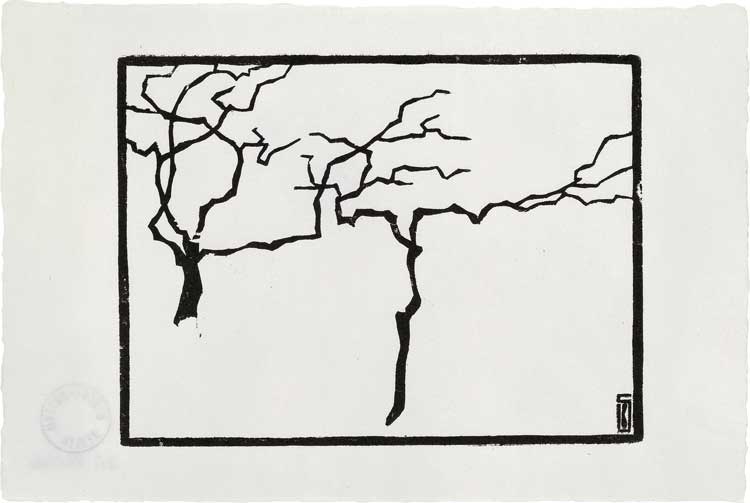

Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, Trees in Winter, 1905. Woodcut. Brücke-Museum.

A clever twist by the curator of the show and director of the museum, Lisa Marei Schmidt, is to introduce a long-forgotten member of the group: Fritz Bleyl. He and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner began to study architecture in Dresden in 1901. Three years later, they befriended fellow students Erich Heckel and Karl Schmidt, later known as Schmidt-Rottluff. The four of them wanted to break with the traditional way of representing the world as seen by their parents’ generation and founded the artists’ collective Brücke in June 1905.

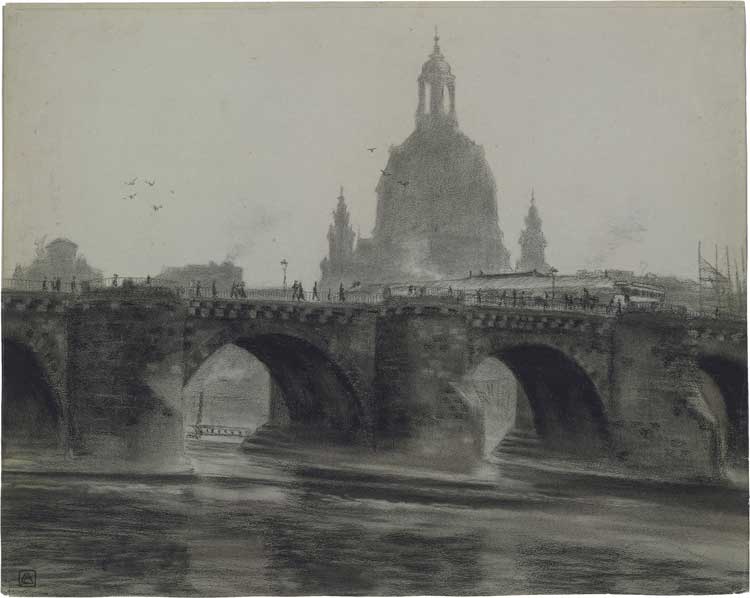

Fritz Bleyl, Augustus Bridge in Dresden with Frauenkirche, 1905. Charcoal and chalk. Brücke-Museum. © Bleyl, Berlin/Solingen.

The first of eight sections in this exhibition is dedicated to the group’s founding and enables visitors to immerse themselves in time and place. There are several images of bridges: drawn with chalk and coal, as prints, as woodcuts. Bridges are a distinct feature of Dresden, but the aspiring artists also saw them symbolically: as a bridge into the future. The pictures are complemented by the group’s founding document showing beautifully crafted letters drawing on the art nouveau style of the time. Also on display are Kirchner’s scenes in a cafe: In the Café II and In the Café III (both 1904), the first a coloured woodcut, the second a plain woodcut. These variations already hint at what is yet to come: the artists’ experimentations with different materials and styles in search of their voice.

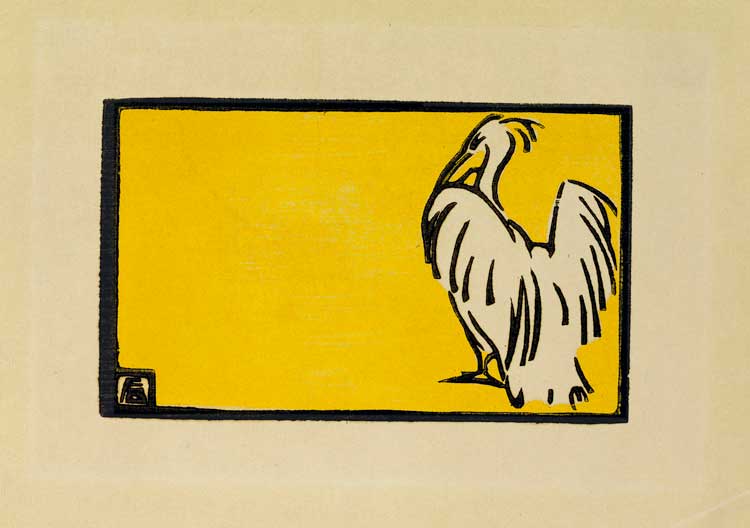

Fritz Bleyl, The Pelican, 1904. Coloured woodcut. Brücke-Museum. © Bleyl, Berlin/Solingen.

The second section of the exhibition allows the visitor to rediscover Bleyl. Unlike the others, he married early and had to earn a living. He became a teacher and left the group in 1907. Yet, he provided them with important impulses as he focused on printing techniques and the applied arts rather than on the production of oil paintings. His work was influenced, among other things, by Japanese art, which was very popular at the time. There is a collection of delightful small images, partly in colour. His Traces in the Snow (1905) is, despite its simplicity, very moving and emanates a soothing calmness. It shows footsteps in the snow lined by barren trees leading up to a house on a rise. Then there is his Willows at a Brook in Winter, Draft for a Stained-Glass Window (1904), which attracts the viewer’s attention because of the sky’s striking orange colour and the peaceful yet uplifting atmosphere it captures.

The beauty of this exhibition is that it enables visitors to discover work they would not normally associate with the Brücke: also, these artefacts are usually in storage at the museum’s depot.

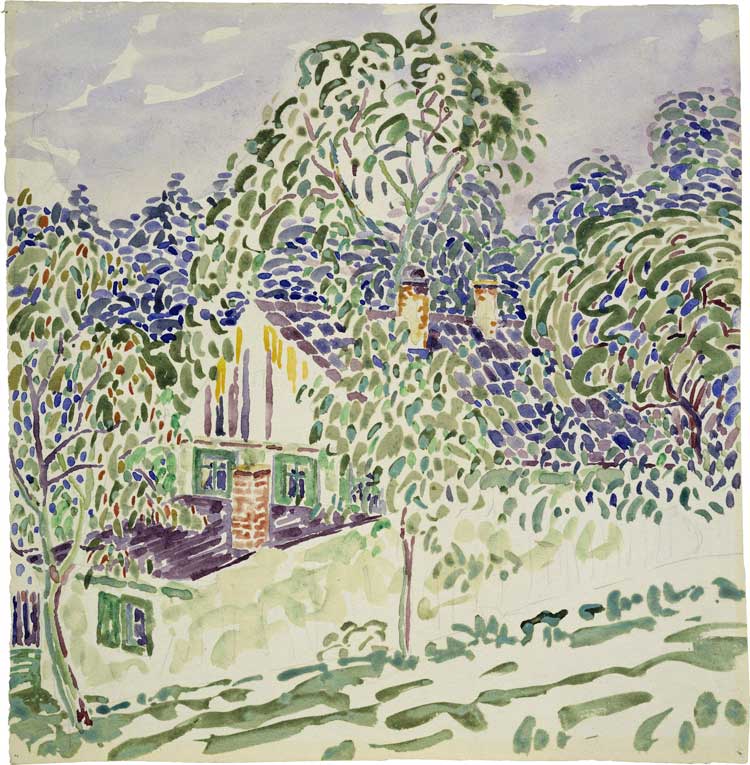

Fritz Bleyl, Farmhouse on a slope, 1907. Watercolour. Brücke-Museum. © Bleyl, Berlin/Solingen.

The wall opposite Bleyl’s small works shows his other influences: pointillism and impressionism. His Farmhouse on a Slope (1907) is a feast of colour. Inspired by pointillism and produced in the summer, this watercolour is light and airy, transporting the viewer to a carefree summer’s day. Next to it are pieces made with black ink and brush on a brown paper, which highlight the different materials the group was exploring.

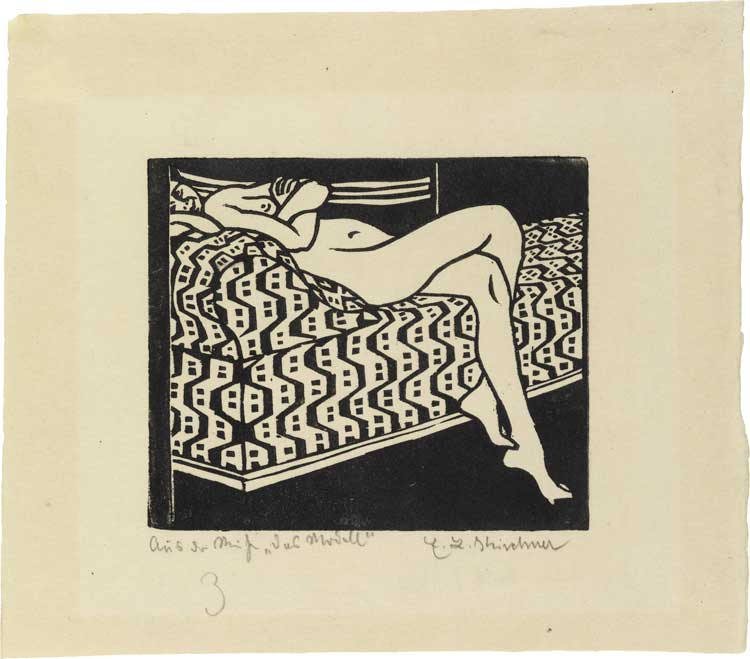

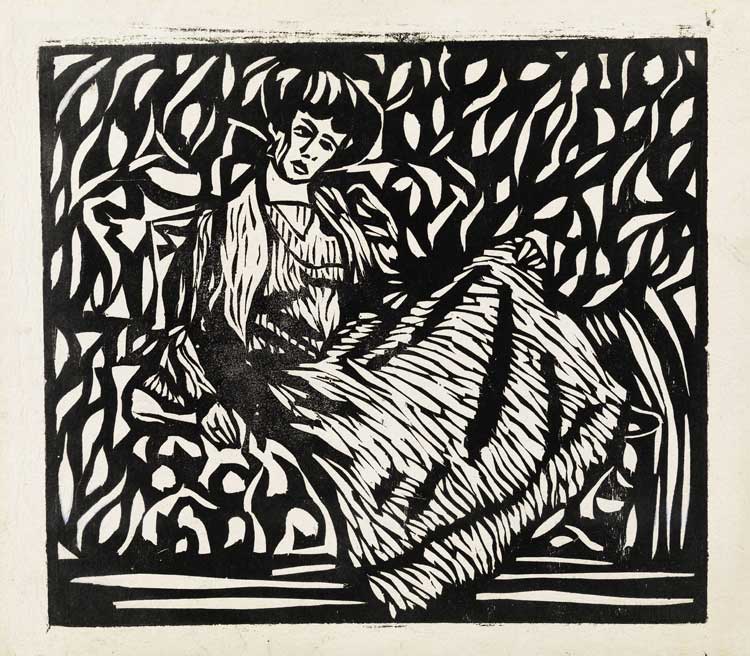

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Nude Girl on a Sofa – The Model 3, from the woodcut series Das Modell, 1905. Woodcut, Brücke-Museum.

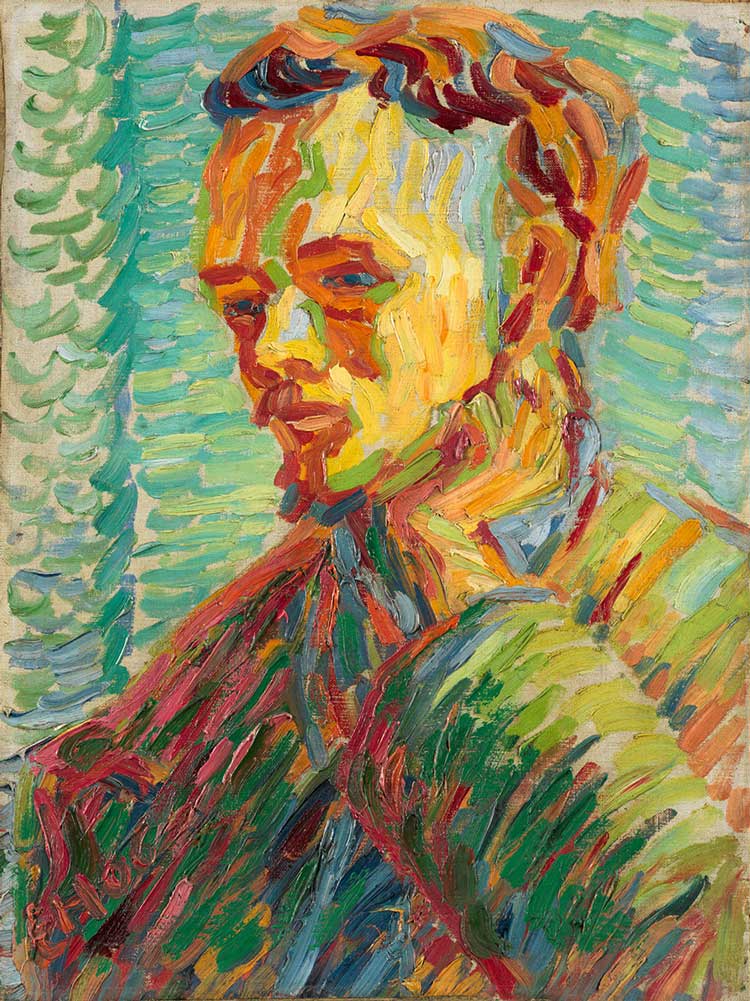

The museum’s largest room looks at the leading artistic movements of the time, which are reflected in the group’s works. Apart from pointillism, impressionism and Japanese art, art nouveau and the paintings by Van Gogh left a mark on them. Art nouveau seeps into Kirchner’s woodcut Nude Girl on a Sofa – The Model 3 (1905). Its sensuous lines, and partly its composition, are reminiscent of Felix Vallotton’s woodcut Laziness (1896), depicting a naked woman surrounded by cushions on a bed, which was shown at the Royal Academy of Arts in London in 2019. The Brücke’s fascination with Van Gogh’s strong, vibrant colours and bold brush strokes is exemplified by Erich Heckel’s oil painting Young Man (1906), featuring yellow, red and bright blue tones.

Erich Heckel, Young Man, 1906. Oil on canvas, Brücke-Museum. Copyright: VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.

Except for these few portraits, the pictures lined up on the room’s long wall show an affinity to landscapes, which later in the artists’ careers is supplemented by motifs from around town, such as the circus and the hustle and bustle of the city. Kirchner’s famous Potsdamer Platz (1914) comes to mind.

In between these pictures from the early years, the curator has cleverly placed works from the Brücke’s later period, which reflects the expressionistic style that came to define the artists’ group. They form a stark contrast to the imagery that dominates this exhibition and highlight how the young men had left their former “masters” far behind and developed their own style. Besides using strong colours and bold shapes, their desire was to produce art quickly, as an immediate response to what they saw in the moment.

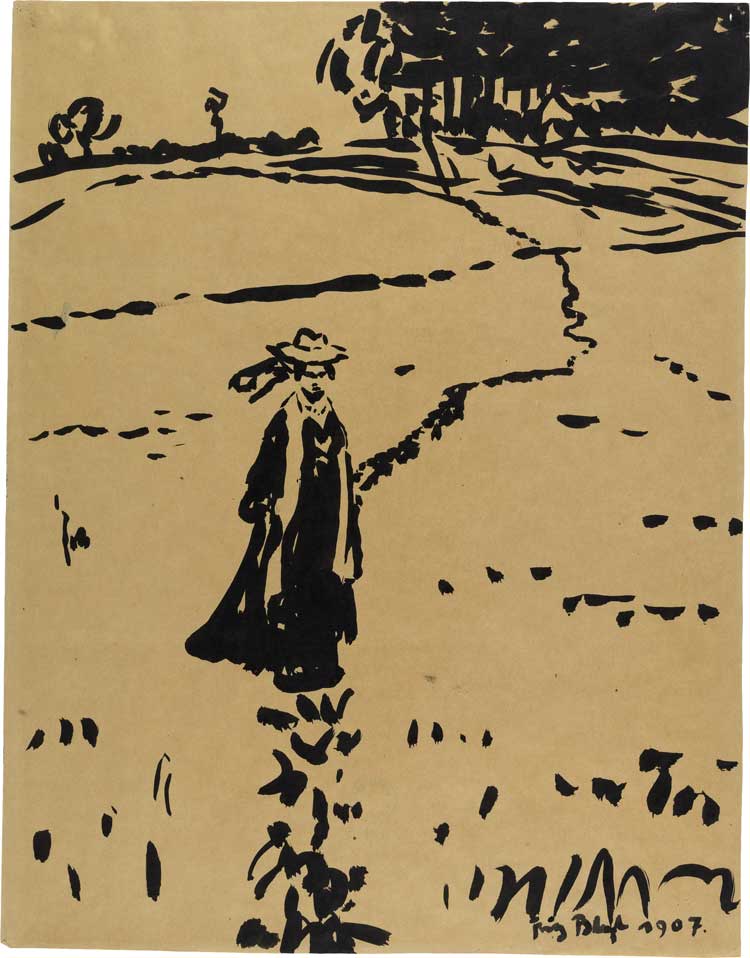

Fritz Bleyl, Woman on the meadow path, 1907. Ink and brush, Brücke-Museum. © Bleyl, Berlin/Solingen.

In this respect, Bleyl differed from the other group members, preferring to take his time to elaborate his art. In addition, he didn’t develop his style beyond his influences, thus not creating a distinct artistic voice of his own, which contributed to him being forgotten.

Before that, though, he was part of the group’s first exhibition in 1906. Breaking with conventions and acting as a collective, the Brücke set up their exhibition in the showroom of a lamp factory. This had the advantage of providing sufficient light and having walls on which they could hang their works. An enlarged image of that space, covering a wall at the museum from floor to ceiling, allows the visitor to get a sense of this key event.

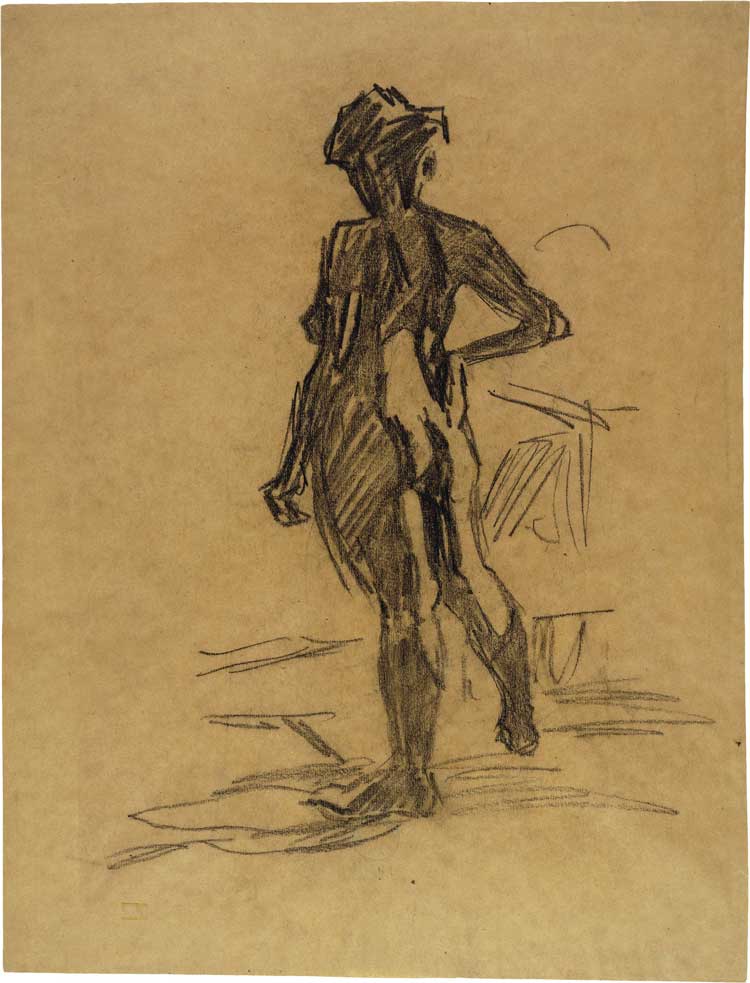

Fritz Bleyl, Female nude from the back, her right hand on her hip, 1905/06. Pen. Brücke-Museum. © Bleyl, Berlin/Solingen.

Further, it demonstrates that the collective was not only driven by art but also guided by the concept of a startup company. This progressive approach to their formation meant they became entrepreneurs as well as artists. This approach included the acquisition of “passive group members”. From today’s perspective, this could be seen as crowdfunding or a friends’ scheme to gather supporters. In exchange for 12 German marks a year, these passive group members would receive a portfolio of three to four original prints. The first of these annual portfolios contained Crouching Nude, Seen from the Back – The Model 4 by Kirchner, Bleyl’s House with Staircase and Heckel’s The Sisters. These supporters were important for the Brücke to gain wider recognition, particularly if they were also art collectors. They all received specifically designed membership cards, which might sound like a minor detail, but the group had also designed for itself a logo, headed paper, invitation cards and posters for its exhibitions, thus creating a corporate identity.

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Dodo, Sitting, in a Striped Dress, 1906. Woodcut, Brücke-Museum.

This encompassing expression of their art is neatly reflected in the visual conception of this exhibition. Like a Gesamtkunstwerk, the wall texts are embellished with ornaments taken from the group’s prints and woodcuts.

By tracing the beginnings of the Brücke, the exhibition provides a fascinating snapshot of a lively period in art history. It brings together a vast array of styles, while presenting the Brücke from a completely different perspective – unlike the previous part of this trilogy, 1910: Brücke. Art and Life, which revealed the inner workings of the group and gave the viewer a better understanding of expressionism.

While the members of the Brücke have regarded themselves as a bridge into the future, this exhibition is certainly a fine bridge into their past.