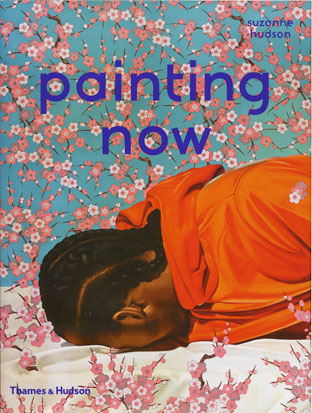

Painting Now by Suzanne Hudson

Published by Thames and Hudson, March 2015

Reviewed by JANET McKENZIE

This new book is an ambitious study and a great achievement. It provides a “roadmap” to current art practice, featuring more than 200 artists from around the world who are challenging and defining the aesthetics of the 21st century. Suzanne Hudson’s text is a vital argument for the importance of painting, and she explores the manner in which the vast field can be reapproached, challenged and reimagined with great alacrity. Her introduction covers the major issues of the past 40 years of visual art, and is followed by six chapters that offer a wide-ranging analysis of the vast area of present-day culture. The sheer volume of artists and ideas is overwhelming, but it is also a book to dip in to, the design of the publication lending itself to such an approach. The chapters enable a critical thread to be maintained through the text: appropriation, attitude, production and distribution, the body, painting about painting, and painters who introduce performance, installation and textiles into their work to critique painting itself.

Painting Now features well-known and emerging artists, including Franz Ackermann, Angela de la Cruz, Urs Fischer, Katharina Grosse, Subodh Gupta, Julie Mehretu, Neo Rauch and Zhang Xiaogang, a range that cannot be done sufficient justice in cultural and personal terms. However, Hudson provides sufficient ideas and information to whet the reader’s appetite to follow up further.

When Charles Saatchi presented The Triumph of Painting at the Saatchi Gallery, London, in 2005, commentators enjoyed, not for the first time in recent art history, the opportunity to herald the rebirth of painting. Saatchi described the significance of new painting as inevitably informed by media, conceptual art and photography, though his critics enjoyed making the assumption that a man who has made his exceptional wealth in the field of advertising must have had his aesthetic judgment formed by television advertising, and that this judgment must be flawed. Saatchi, however, was quick to point out that from 1995-2005 only five of the 40 Turner Prize nominees had been painters.

In an interview in 2013 with Young British Artist Mat Collishaw,1 whose contemporaries at Goldsmiths included Damien Hirst, Tracey Emin, Sarah Lucas, Michael Landy and Gillian Wearing, he recalled that their preferred materials as students were light bulbs, aluminium, string and polythene: indeed, anything but traditional materials. The most radical thing an artist can do now, he claimed was “to paint with oils on canvas”.2 A revival of painting by Collishaw and Hirst (who is included in Painting Now) indicates the significant cultural shift away from the gaudy consumerism and nihilism that artists of the 90s once championed. Yet there remain numerous examples of gaudy painting in the new study, and the work of the Chinese artists chosen – such as Zhang Xiaogang – reflects the political pop and cynical realism championed by the international art market in the late 80s and 90s in preference to the more poetic painting movement being created by artists such as Liang Quan, Liu Guofu, Yang Liming and Guan Jingjing.3,4

A student of Sigmar Polke, and possessing an original reinvention of the German Expressionists’ immediacy and passion for painting, Ackermann is an important artist in this context. His painting challenges the conventional use of materials, using a wide range of methods to heighten the reception of the painted surface. In order to conjure the chaos of the surveillance culture, he employs cut materials, collage, pencil and neon paint that cannot be reproduced digitally, to retain the work as a powerful entity. Describing his impulse to achieve “total freedom” to express his questions and doubts for an image of the present, he asserts: “This is the only single colour field with colours that can not be reproduced by a bloody iPad. The works cannot be transmitted digitally, in an accurate form to Hong Kong, to Sao Paulo, or wherever. It just doesn’t work. This is very important to me; you don’t get it if you don’t come to see the actual work.”5 In Ackermann’s painted works, the dichotomy of fear and freedom, of sameness and exotica, of crowds and solitariness are all to be found in the processes he employs.

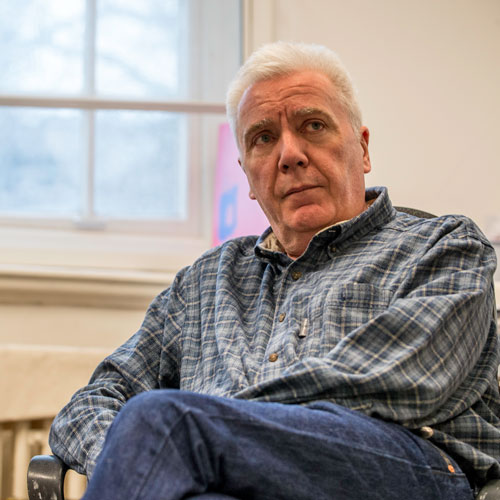

Christopher Le Brun, President of the Royal Academy, spent time working in Germany in the late 80s where he met Anselm Kiefer and Georg Baselitz, as well as the Italian transavantgarde artists Sandro Chia and Francesco Clemente, all of whom rejected the tenets of conceptual art and, by reviving figuration and symbolism, sought to restore myth, mystery and magic to contemporary art. From the late 80s, Le Brun’s work possessed a sense of spiritual abundance, which on close inspection in painterly terms, is in fact very understated. The brushmarks are nonetheless assertive and the works possess the wholeness akin to the literariness he aspires to portray. I visited him in his studio in south London last year and, in discussion, we referred to Australia, the exhibition at the Royal Academy towards the end of 2013. Among the terminology of Australian Aboriginal art, “meaningful mark-making” refers to everything that is implied by the imagery that makes it significant. The outward appearance of a richly informed work of art in the end is something fresh and alive.

In this context, Le Brun observed: “I find it extremely curious that humans are so interested in this activity [of painting]. When I saw the paintings in the Australia show, I thought what was particularly moving was painting’s extreme longevity. Clearly, it is one of the fundamental attributes of our species’ identity. Whether it is Michelangelo or Titian, it is a constant driving force at all times, in every picture, by every amateur, every child. You feel something basic in the act of painting that distinguishes it from the chaos of surrounding images. You always notice something painted or drawn – it always calls to us. This is why paintings that are overburdened with message or prescription are less interesting to me than those where you sense that essential enigma.”6

Many artists, who trained in painting and drawing in the 60s and 70s, such as Rootstein Hopkins Chair of Drawing Stephen Farthing, found the subsequent dominance of conceptual art challenging. Farthing recalls: “Just about everything in my life was orientated towards my drawing and then painting, not just in terms of what I observed before me, but within my thoughts. I drew to organise and inform the thoughts that enabled my painting. I painted because it gave me a physical, intellectual and emotional sense of wellbeing and there was a receptive audience for my work. By 1990, painting was no longer fashionable and my peers who were sculptors, video and performance artists took centre stage. I made a, probably unwise, decision, to stick with painting, and for 15 years I took photographs, began to use digital technology and probably drew, in the old-fashioned perception of the word, less. The end product, however, was always painting, but which no longer had much of an audience. Today, I paint because I love painting, remain interested not so much in it as a craft but the possibility that, through painting I will break new ground, not simply as a modernist history painter, but as an artist”.7

For Anita Taylor, founder of the Jerwood Drawing Prize, and an important art educator: “The act of drawing is fundamental to the process of both creative development and as a means to encounter and examine the world. The heart of my practice revolves around the culture of reinterpretation and re-evaluation of experience through a sifting of the past and of reverie within the present.” These thoughts are visualised or embodied through the act of drawing that prepares the way for her large narrative paintings.

Taylor continues: “The cathartic moment of pinning down a transitory moment is elusive, as ephemeral as catching a glimpse of oneself in a mirror. It is a moment that is both immediate, but not instantaneous like the snap and click of the single photographic lens. More a lens on the world that adapts and adjusts perspectives, focus, location and distance – the perceptual basis of seeing – collating information from different sources, perceiving and rendering an equivalent depiction”.8

Painting Now makes a valuable contribution to commentary on the visual arts and culture in the present.

References

1. Mat Collishaw: This is Not an Exit. Interview by Janet McKenzie, Studio International, 3 April 2013. studiointernational.com/index.php/mat-collishaw-this-is-not-an-exit

2. Ibid.

3. See Painting for Stimulation: Guan Jingjing by Janet McKenzie, Studio International, 7 January 2014. studiointernational.com/index.php/painting-for-stimulation-guan-jingjing-solo-exhibition

4. See Moving Beyond – Painting in China 2013 by Darran Anderson, Studio International, 9 September 2013. studiointernational.com/index.php/moving-beyond

5. Franz Ackermann interview with Janet McKenzie, White Cube Gallery, London, 21 January 2014.

6. Christopher Le Brun interviewed by Janet McKenzie, London, January 2014.

7. Stephen Farthing, email interview with Janet McKenzie, 2 March 2015.

8. Anita Taylor, email interview with Janet McKenzie, 5 March 2015.