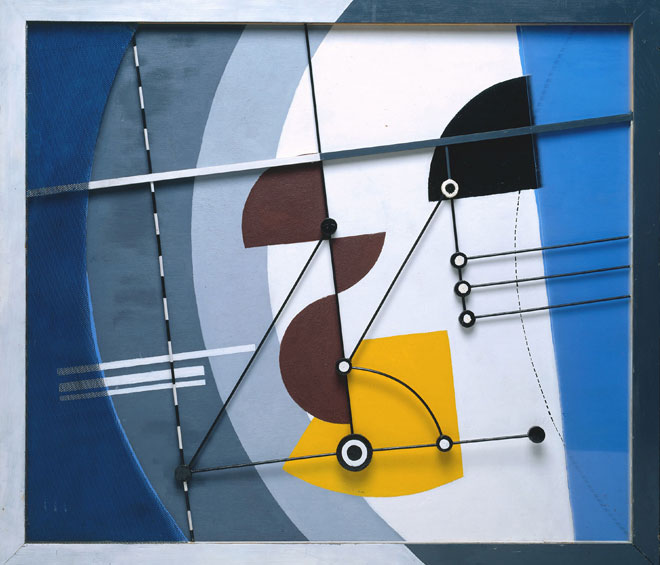

John Piper. Construction, 1934, reconstructed 1967. © The Piper Estate.

Tate Liverpool

17 November 2017 – 18 March 2018

by JOE LLOYD

Nothing galvanised John Piper (1903-92) like the second world war. Commissioned by Kenneth Clark’s Recording Britain scheme to paint softly propagandistic depictions of England’s built heritage, Piper refined a style he had previously used for rococo fantasias into something romantic and nostalgic. As the bombs fell on the cities, he captured their ruined churches through a nocturnal gauze, their roofless naves standing as testament to the country’s struggle. When asked, in 1940, to paint Bristol’s air raid precautions control room in Bristol, he produced mysterious, spatially complicated works fixated on painted maps and wall markings ornamenting otherwise colourless corridors. Few artworks make the domestic aspect of the war, the way it is practised away from the battlefields, so immediate and yet so alien.

John Piper. Abstract I, 1935. Oil paint on canvas on plywood, 91.7 x 106.5 x 5 cm. Tate. Purchased 1954. © The Piper Estate / DACS 2017. © National Museum of Wales.

These heart-tugging works appear towards the close of the Tate Liverpool’s John Piper retrospective, which devotes much of its wall space to his work from the 30s. On entering, you could be forgiven for asking whether you had crossed the wrong threshold: the exhibition begins with a series of abstract constructions, which Piper created after a 1934 trip to Paris. These were exhibited in London alongside Joan Miró, Wassily Kandinsky and others.

It is unlikely that Piper benefited from the juxtaposition. One of these Abstract Constructions (all 1934), crisscrossed with wooden dowels that resemble rigging, looks like a navigation device; the artist then collaged sand into its dull beige paint, as if to ensure the viewer grasped its nautical inspiration. In a 1935 interview on BBC radio, he declared that abstracts should look “like nothing on Earth. They are not meant to be like anything. They’re just arrangements of shapes and colours.” Alas, with their embrace of the sand and sea, Piper’s own are all too terrestrial.

-1938.jpg)

John Piper. Black Ground (Screen for the Sea), 1938. Oil on canvas, 121.6 x 182.8 cm. Collection: National Galleries of Scotland, purchased 1978. © The Piper Estate / DACS 2017. Photograph: Antonia Reeve.

Piper saw these works, of which few survive, as mere “exercises,” and it is not hard to feel that his heart wasn’t in them. Nevertheless, he trundled along in abstraction for several years. In paintings such as Abstract I and Abstract (both 1935), he hit on a strange combination of rigid forms and breezy arrangements, with motifs derived from the facades of classical architecture jostling alongside corners of beach and sky.

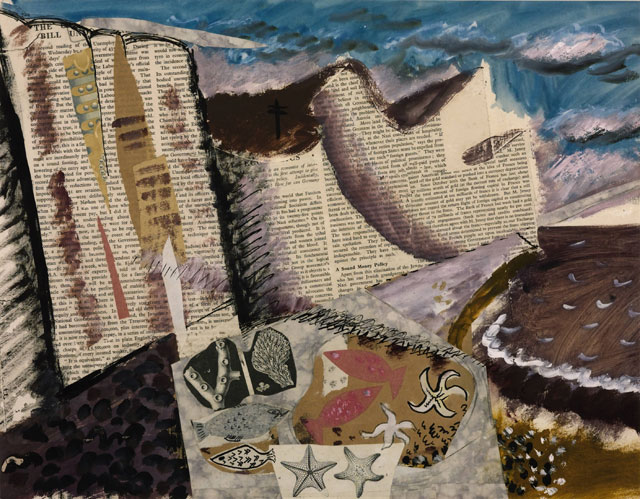

John Piper. Beach with Starfish, c1933-4. Gouache, printed paper and ink on paper, 38 x 48.5 cm. Tate. Presented by Lady (Charlotte) Bonham Carter 1988. © The Piper Estate.

Two years later, he created the bizarre free-standing Beach Object (1937), now lost but represented by a photograph, in which abstract shapes were turned into a cluster of kitschy oceanic sculptures. In 1938, he contributed an abstract mural for Berthold Lubetkin’s seminal Highpoint Two building in London. But his views on the mode soured soon afterwards. The next year, in the art magazine XXe Siècle, he wrote: “Abstraction is a luxury. Yet some painters today indulge it as if it were the bread of life.” A hint of bitterness, perhaps, for a style with which he was never quite at home?

Not that his prewar figurative work is any more comfortable. A room of early work has a similar sense of a not-untalented artist struggling to find his métier. View from a Window (1933) reimagines Matisse for the drab Atlantic, with the leisurely sloops replaced by an industrial vessel with a belching chimney. This would be a pleasant homage to the greater artist had Piper not stuck doily-esque fabric to the paper to simulate curtains, a move that pushes it into gothic thriller schlock. In the more successful Fishing Boats near Newhaven (1933), meanwhile, Piper takes up the language of the post-cubist Georges Braque, crafting a space through a set of curving lines and flattening features such as boats and fishes into simplified forms.

John Piper. Harbour Scene, Newhaven, 1936-1937. Ink, gouache and collage on paper, 60.9 x 81.3 cm. © The Piper Estate / DACS 2017. Image courtesy: Private collection.

It was Picasso, though, who most obsessed the early Piper. A sketchbook of 1932-34 is filled with reproductions of the maestro’s works, placed alongside Piper’s own attempts. In collages such as Beach with Starfish (c1933-34), he imitates Picasso’s habit during the 1910s of sticking printed text on top of paint, but does so with less subtly and purpose. There is a curious paradox in these works, where Piper depicts much clearer, more conventional landscapes than his idol and yet displays less logic in his apportion of materials to space. Why, for instance, are his cliffs fashioned from magazine paper?

These phases offer some divertissement alongside the failures, but often leave one wanting. War had provided the perfect locus for Piper’s melancholia. After it, his paintings regressed – witness Rowlestone Tympanum with a Hanging Lamp (1951), a garish debasement of Picasso that prefigures David Hockney’s nightmarish 1980s output. The style Piper mastered for structures ruined, or under threat of ruin, loses its charge when applied to the anodyne Regency terraces of Brighton.

But Piper’s long late period did see him create work of another stripe, much of it his worthiest. In 1937, he had followed John Betjeman and Paul Nash in creating the Oxfordshire edition of the Shell Guides, a popular, often wittily written series of books exploring the architectural sights of the British counties. Here, he adopted a wistful prose pared with equally romantic photographs of buildings and landscape. A slide in the exhibition shows these beguiling, sometimes witty, images of tumbledown farmhouses, ivy-coated churches and trees overburdened with tobacco and tea advertisements. In 1949, he joined Betjemen as co-editor of the series before later becoming sole editor, and so continued to shape the series’ aesthetic. His work on the guides counts among his finest contributions to British culture.

John Piper. Painting, 1935. Oil on canvas on board, 40.7 x 30.2 cm. National Museums & Galleries of Wales, Cardiff. © The Piper Estate / DACS 2017. © National Museum of Wales.

There is also much to enjoy in Piper’s gradual shift towards the applied. This had begun in 1936, when, along with Robert Wellington, he founded Contemporary Lithographs Ltd with the purpose of creating prints to adorn schools. The two Nursery Friezes (1938) take the boats, beaches, clouds, churches, seafront homes and lighthouses of his paintings and place them into a pleasing jumble. By the 50s, he was redeploying the Georgian motif of his abstracts into a set of textiles for forward-thinking design company David Whitehead Ltd, and, freed from the framing of the canvas, they are granted a second, more fecund life.

Perhaps Piper’s most distinctive legacy came when he turned to stained glass, often crafted with the master glass-designer Patrick Reyntiens, and the apotheosis of a long-lasting interest in English medieval architecture. From the abstract shapes of his large-scale work at Coventry to the bucolic nature of his single window at Oxford’s exquisite St Mary Iffley church, we find Piper at his most individual. Visitors to Tate Liverpool would be advised to walk across town to the Metropolitan Cathedral, whose bland concrete interior is enlivened by the rich colours of his glass cupola.

It is a shame – although, given their forms, perhaps an inevitability – that the Tate’s exhibition is so heavily weighted against these later explorations beyond the canvas. Piper’s vision seems to come most alive in collaboration or commission, rather than when left to his own devices. Yet there is something fascinating in watching the young painter jump from style to style with mixed success, forever attempting to squeeze Paris into Britain’s south-east coast.