Ikon Gallery, Birmingham

15 March – 4 June 2017

by MATTHEW RUDMAN

The ocean floor is a mysterious place, we are often told, more alien than the surface of the moon. But, for Jean Painlevé, coastal shallows, and the familiar crabs, shrimps and snails that call them home, held just as much mystery. Painlevé (1902-89) was a French documentarian who, over his six-decade career, made more than 200 short films, chronicling key moments in the lives of marine animals, using novel technologies to reach microscopic scales.

Despite his prolific output, Painlevé is little known outside France, and this concise exhibition at Birmingham’s Ikon Gallery is the first solo show in the UK for this fascinating and eccentric artist. The four documentary films on show range in subject matter from seahorse childbirth to hermaphroditic snail orgies, melting multicoloured crystals to a 1927 circus show puppeteered by Alexander Calder. The films are accompanied by a set of microscopic marine photographs, and a collection of seahorse-themed jewellery designed by Painlevé’s partner Geneviève Hamon.

Documentary is only an approximation of what Painlevé’s films are striving to achieve. Having studied biology at the Sorbonne in the 20s, he does indeed cover a lot of scientific ground, describing in intricate detail the interior structure of the male seahorse’s egg pouch, or how the hermaphrodite acera snails mate. However, he also seeks to entertain, and his idea of these two goals being interrelated was novel for his time. His camera, paired with a microscope, uncovers hidden beauty in the translucent hoods of fluttering sea snails or the curling ribbed tails of the seahorse, beauty spiced up with unexpectedly comedic narration: the news that these postnatal seahorses are uncomfortably gassy was met with peals of laughter among the assembled viewers.

Raised in Paris, Painlevé was frequently taken on trips as a child to the region of Finistère in Brittany, earning the nickname the “Pêcheur de Triton” (the “newt fisherman”) for his interest in marine life. While at the Sorbonne, Painlevé was a member of the French Union of Communist Students, through which he became familiar with avant-garde film and the surrealist movement, meeting such greats as Luis Buñuel, Sergei Eisenstein, Fernand Léger, Man Ray and Alexander Calder. We see echoes of these influences in his close-up photography of lobsters, a favourite surrealist motif, but while the Paris of the 20s and 30s was a crucible of competing movements, Painlevé stood at a distance, defying any easy categorisation.

Over the course of his career he eschewed the exotic; he rarely filmed marine life that wasn’t readily available for capture in the shallows of the Brittany coast. What excited him about cinema was its capacity to make the familiar new again, to guide attention to organisms normally deemed unworthy of it. His subjects are urchins, snails, squid, hardly exciting on paper. However, with the relatively new cinematic powers of magnification and slow motion at his disposal, Painlevé was able to transmute a crab claw into a monstrous visage, the nose of a shrimp into fanning feathers of impossible delicacy.

His 1934 film L’hippocampe (The Seahorse) is the best-known work on display at the Ikon. The 14-minute black-and-white film explores the unusual reproductive cycle of seahorses, where the female gives the male eggs for both fertilisation and birth. The film is replete with scientific detail: Painlevé’s narration guides our attention as he slows the film to a crawl, revealing the drumming heartbeat of a newborn seahorse.

In 1948, Painlevé proclaimed his “Ten Commandments” on the practice and theory of film-making, one of which states: “You will not make documentaries if you do not feel the subject.” In L’hippocampe this drive is readily apparent: Painlevé marries his biology lessons with emotive, anthropomorphic description: the narrator ponders the male’s wide eyes, anxiously waiting for the right moment, and lingers on the rhythms of his contractions, which are pained and distressing. The rapid cutting of labour gives way to long, calm shots lingering on the beauty of the translucent newborn creatures.

Despite commonly being pictured wading around tide pools in Brittany, Painlevé was a cosmopolitan man, unafraid of commenting on, and profiting from, his own work. He remarks on the function of sex and gender in seahorses: “The seahorse was for me a splendid way of promoting the kindness and virtue of the father, while at the same time underlining the necessity of the mother. In other words, I wanted to re-establish the balance between male and female.” Alongside this film is displayed a collection of jewellery, designed by Hamon (as is the wonderful nautical wallpaper adorning the room in which they are displayed), and launched in the hope of capitalising on the success of L’hippocampe. One can imagine the vital, contemporary meanings these gracefully intertwined seahorse necklaces, bracelets and earrings would have taken on for the women who wore them in 30s Paris.

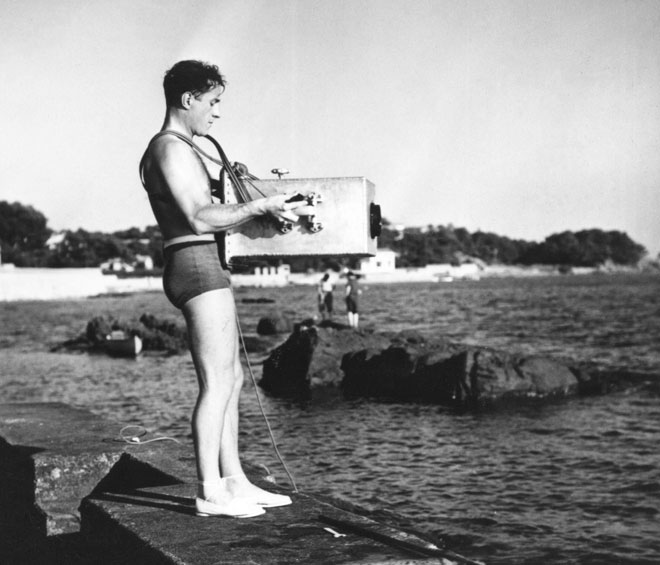

A technician at heart, Painlevé built many custom camera rigs of assorted waterproof boxes and panes of glass, both for filming in the wild and in the studio, the latter of which he preferred as it granted him more control over his subjects. As such, the backgrounds in his films are often sparse, which serves to accentuate the magical details and movements his camera records. In Acera or the Witches’ Dance (1978), the snails are subject to long static shots against plain backgrounds of green and black, casting their luminous propulsive hoods in brilliant detail.

Transition de Phase dans les Cristaux Liquides (Phase Transition in Liquid Crystals), also from 1978, attests to Painlevé’s technical prowess and gestures to his work beyond the aquarium. The film is a mesmerising journey through various states of matter, our perceptions of scale oscillating from the grand and celestial to the small and kaleidoscopic. Rough shards of crystal melt into psychedelic rivulets of dye, as metallic circles expand and contract, resembling circular fields or reservoirs seen from the air.

Beyond film and photography, Painlevé recognised the importance of music in animating his subjects and engaging his audience. Phase Transition is accompanied by a brilliantly spooky, off-kilter soundtrack by electronic music pioneer François de Roubaix, while Acera or the Witches’ Dance, 1978, is set to the music of Pierre Jansen, whose anarchic horns inject some energy into proceedings, synchronising with the snails’ dove-like flapping.

This exhibition is an intriguing introduction to an artist deserving of more attention. There is visual poetry in these peculiar – and often funny – films and photographs, and it’s a shame there isn’t room for more of them. These works communicate Painlevé’s essential enthusiasm and childlike curiosity about the quotidian natural world around us: they bid us to look, and look again, more closely now.