L’Étrangère, London

4 November – 16 December 2016

by VERONICA SIMPSON

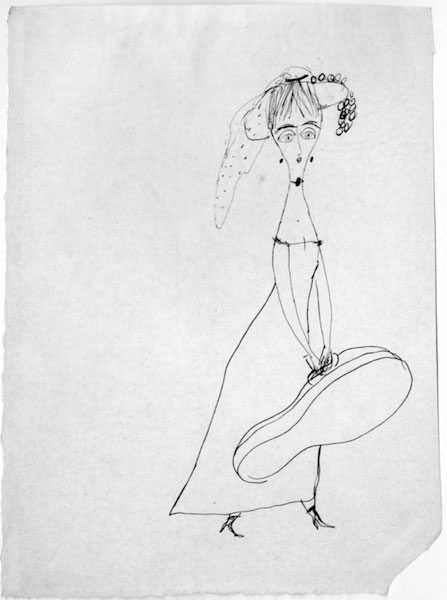

Like many others who have been to shows featuring Franciszka Themerson’s work, I find myself struck by the deep familiarity of her vivacious, expressive drawing style, despite thinking I knew next to nothing about her. I recognise her visual language from the most memorable, distinctive children’s books of the mid-20th century, a language that has inspired generations of literary illustrators since.

But Themerson (1907-88) was so much more than an illustrator, as the excellent Camden Arts Centre exhibition of spring 2016 demonstrated; it revealed much of Themerson and her husband Stefan’s impressive mid-century, multidisciplinary oeuvre, including experimental film, photography, publishing, poetry and theatre design. But her artworks were missing from that show, which makes this a nicely balanced response: it shines a light on her unique talent, her ability to conjure life and emotion out of a single line; or convey a whole interior landscape through her rich, densely worked paintings.

After completing degrees in music and then fine art, in Warsaw, she and Stefan (a poet and philosopher, among other things) made avant-garde experimental films and photograms and founded the Polish Film-Makers Co-op, while earning a modest living from their remarkable children’s books. In 1938, they moved to Paris, but were separated during the war, with Franciszka coming to London and Stefan staying in France. Reunited in London, in 1942, she and Stefan rekindled their film-making and then, in 1948, founded what is often described as the most important postwar avant-garde imprint in London, Gaberbocchus Press. Their writers were also their friends, and included Jankel Adler, Kurt Schwitters, Raoul Hausmann, Guillaume Apollinaire, Raymond Queneau, Bertrand Russell and Stevie Smith. But their most celebrated publication was the first English translation of Ubu Roi by Alfred Jarry, in 1951, for which Franciszka provided illustrations, masks, set designs and, ultimately, in 1970, a comic-book version that is still seen as shocking and fresh, nearly 50 years later.

She was the daughter of an artist and a musician, surrounded throughout her life by intellectuals, poets and philosophers, so it is no wonder that her work fizzes with ideas and intellectual energy.

In addition to her collaborations, she was celebrated in her lifetime as a painter, with solo shows in New York, London and Warsaw, culminating in a major 1975 retrospective at the Whitechapel Gallery. But although she was clearly appreciated by gallerists and her peers, and went on to be featured in exhibitions through the 90s and noughties, she may have suffered somewhat from the tendency of late-20th-century art historians to overlook many influential women. Certainly, L’Étrangère director Joanna Mackiewicz-Gemes thinks so. She said: “Women were sidelined in the 60s, 70s and 80s. Women were playing second fiddle. I wanted this to be about her contribution … to show her in her own right.”

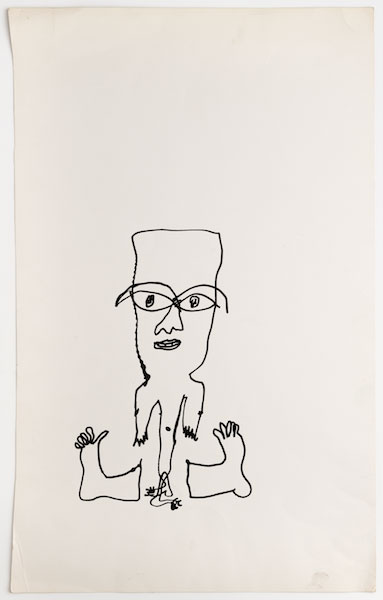

However, there is no sense that Themerson herself felt sidelined. Gemes says: “With Stefan it was very much on equal terms. They were defined as the Themersons. They were famous for their films. But in researching this exhibition, I was amazed to see so many drawings and paintings from Franciszka. What I wanted to show through this selection is the strength of her line. Her medium is the line.”

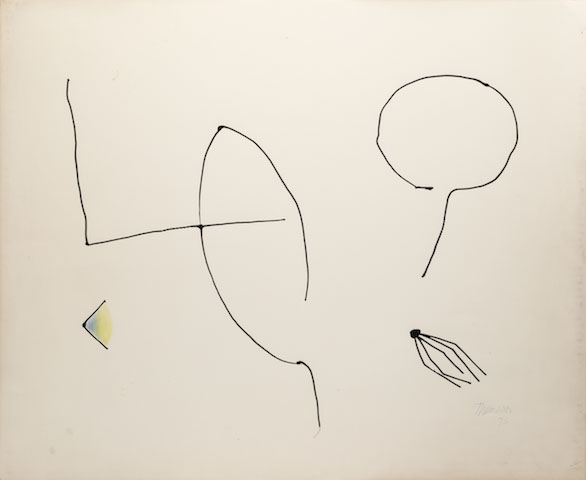

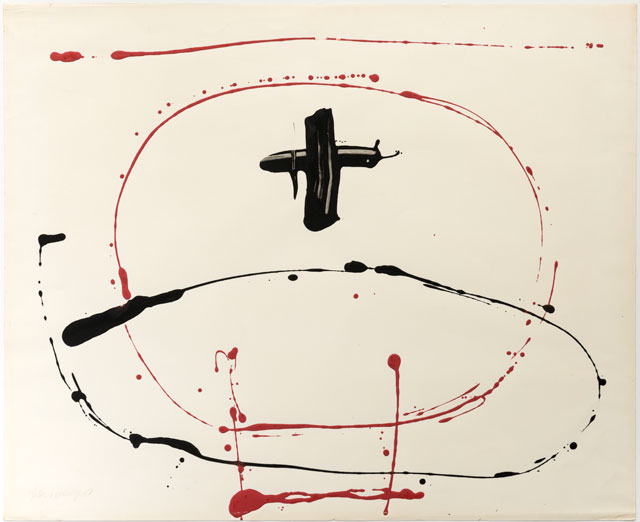

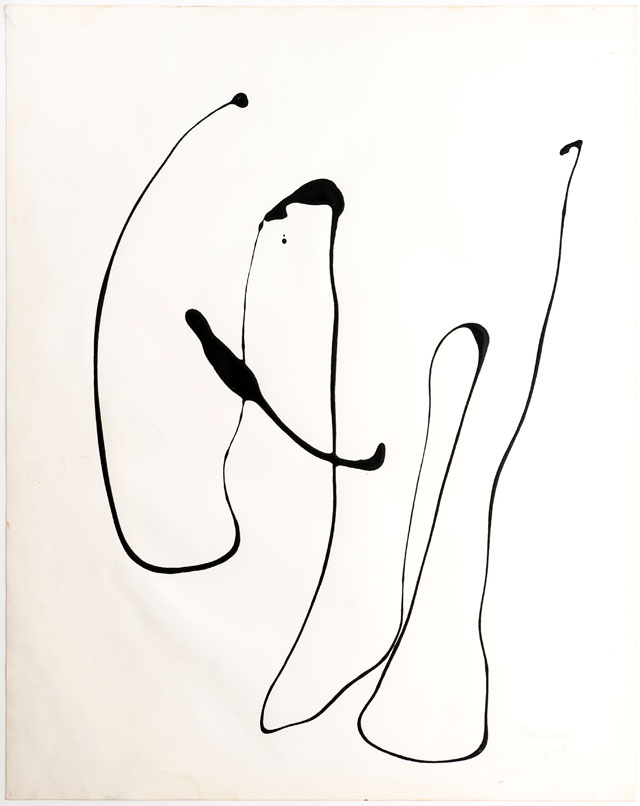

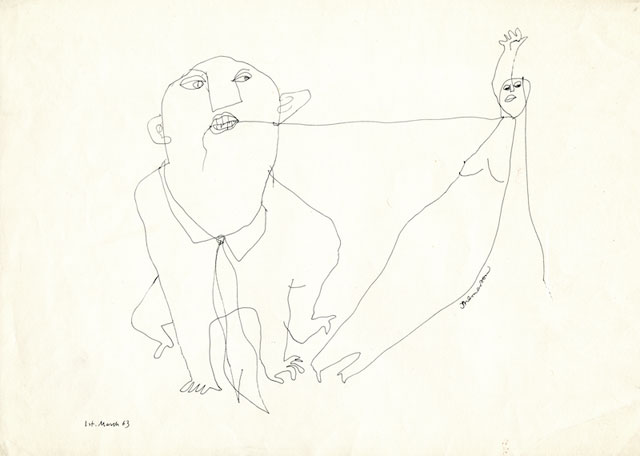

This line is manifested most eloquently in her drawings, but is indisputably present in the paintings, of which there are only three here. Gemes has chosen to hang the paintings in the two main rooms, framed by groups of drawings and also calligrammes – spare, yet dynamic expressions of line and movement, paint and emulsion; painted sketches. In this way, she is highlighting the relationships between the three styles and the evolution of that line. Themerson called her work “Bi-abstract” – a mixture of figurative and abstract. Even in the most abstract of calligrammes, something human, characterful is lurking. Notably, there is little attention paid to gender: through this very abstraction, these figures, whether embracing, solo or clustered, are genderless - apart from the very male protagonist in Party Games (1963); here, a great ape of a man, all looming head and dragging, simian arms, holds a line of string gripped between his teeth, with which he seems to be dragging – or choking - a willowy, resistant woman by her neck. Party games? Not fun ones, clearly. Again she shows her ability to conjure an entire social scenario with a few strokes of her pen.

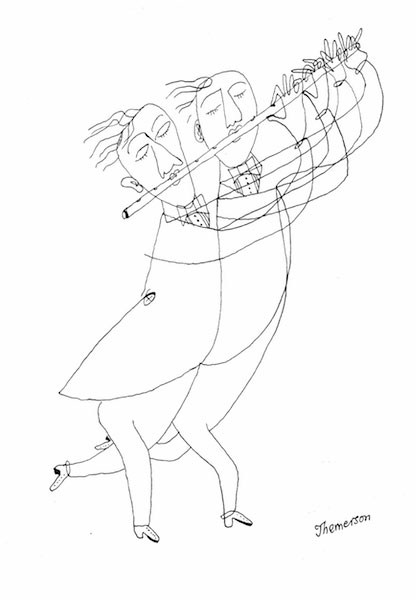

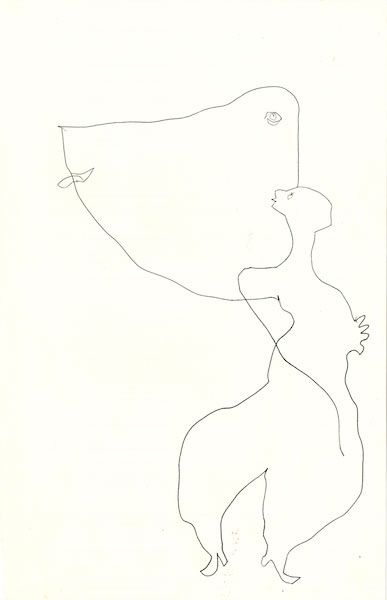

A cluster of four drawings in the second room – which Gemes titles Traces of Living - are particularly striking. In Mutuality Resolved (1960), a playful landscape of voluptuous lines becomes a cluster of peering people, conjured through the slightest gesture – a pair of eyes, a nose, or outstretched hands emerging from an undulating profile. [Traces] Two Figures with Outstretched Arms (1961) shows her bi-abstract technique at its most essential – the two bodies are barely recognisable as such, but their arms reach out to each other, while their distorted upper bodies – elongated, two-sided heads - play a compelling game of attraction and repulsion. There is nothing so ambiguous about Attraction (1961): with just a few strokes of her pen, she sums up the very shape and essence of desire, without getting bogged down by form.

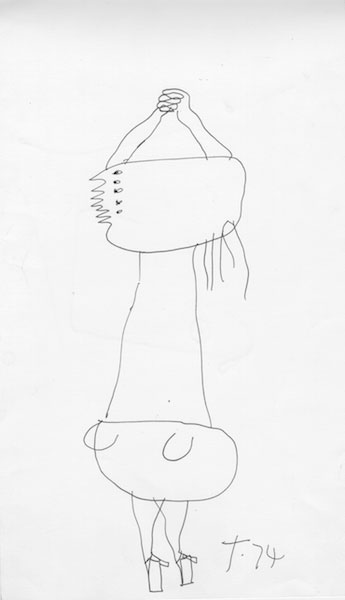

Most of the drawings are from the 50s and 60s. A handful more sketches are present in the furthest room, along with the seminal books she and Stefan published. These drawings dip into her deep love for and knowledge of music and musicians. Whimsical, lightning sketches, they include Double-flute (third version) (1955), whose musicality (as well as the musicians) practically floats off the page; and Sospiroso (1955), which depicts, from behind, the plump bottom and tenderly inclined head and legs (even the stool legs “lean in”) of a cello player, caressing the instrument with his bow.

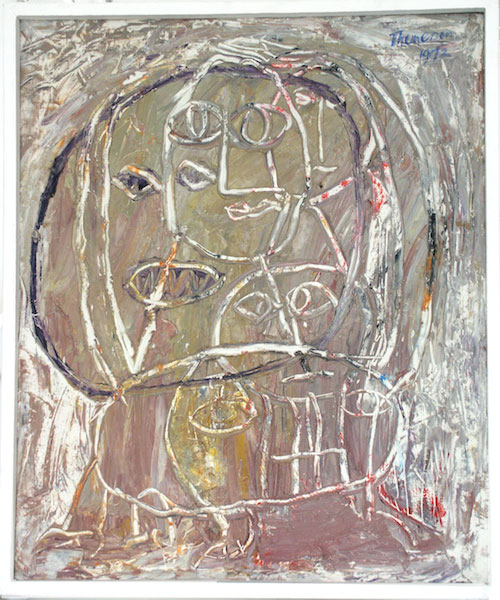

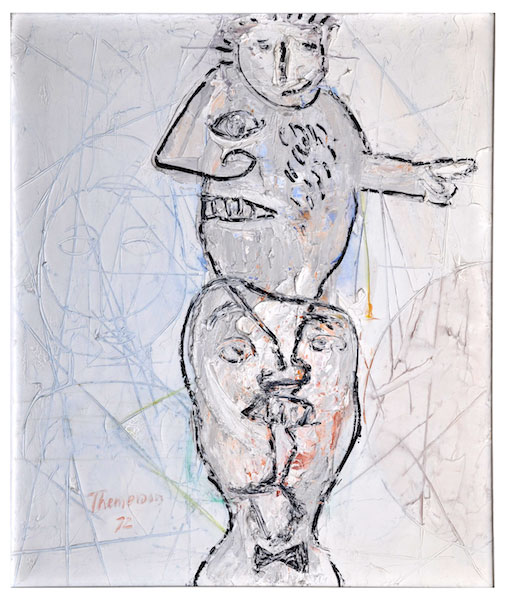

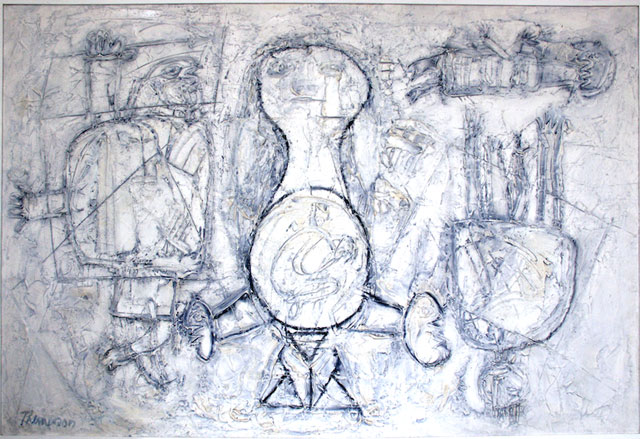

The three paintings here are intended as anchors for the show. All are from 1972. They are complex, densely worked and richly layered but still with that graphic clarity that rewards sustained contemplation.

If a picture paints a thousand words, then Coil Totem (1972) is surely a novel – possibly a trilogy. The longer you stare at this painting, the more mesmerising it becomes. The fleshy, sculptural immediacy of the central figure is somehow both dense – with its strong, graphic outline - and also light. Its face beams a defiant certitude in thick, white paint; the mournful, hunched figure coiled in its belly adds to the poignancy of that facial expression. Other figures crowd on to the canvas, one floating sideways, another upside down (preceding Baselitz), but rendered with such confidence, however palely, that they seem utterly present, as well as spectral. “Some say this is a masterpiece,” declared Gemes. I wouldn’t disagree.

Themerson is one of those characters, like Jean Dubuffet, who are very much of their time, yet without having advocated, associated with or spearheaded any particular movement, so it’s great to see her fierce humour and independence of spirit championed; the 12 Star Gallery, at Europe House, ran a very successful show of her paintings in 2013, featuring – and named after - another work that is shown here: A Person I Know (1972). It seems to manifest a physical battle being waged with paint and stick as she wrestles with the tensions that propelled her as an artist, which she summarised thus: “It seemed to me that the interrelation between these two sides: order in nature on the one side, and the human condition on the other, was the undefinable drama to be grasped, dealt with and communicated by me.”

.jpg)

-copy.jpg)