Henry Moore Institute, Leeds

21 November 2013 – 16 February 2014

by ANNA McNAY

The works on display fall into several distinct categories, but each overlaps with the next. So, for example, the two large-scale sculptures, or machines, that dominate the space are documented on the surrounding walls with diagrams. There are diagrams, too, for other outdoor works, including Polarities (1972), for which he recreated drawings by his daughter and father, with bright red flares, in the sky over Bridgehampton, New York. Other sky works represented include Whirlpool – Eye of the Storm (1973), in which Oppenheim employed a small aeroplane to turn circles in the air, emitting white smoke and creating a three-quarter mile diameter vortex, filmed by another aircraft. Both photographs and a short film are shown to document this surreal event.

Three of Oppenheim’s firework signs – as the name suggests, words written as pyrotechnic placards – are to be recreated in front of the gallery during the run of this exhibition: NarrowMind, Mindless Less Mind and Mind Twist will be ignited at 17.30 on 27 November, 11 December and 15 January respectively. Also to be activated during the show are the two aforementioned mechanical sculptural constructions, Vibrating Forest (1982) and Launching Structure #3 (An Armature for Projection) (1982). The former is the culprit of the fairground aroma seeping through the gallery. Built to hold about nine sticks of the sugary confection, inserted horizontally so as to face a large industrial fan, with firework rockets aplenty stacked in buckets all around, goodness only knows quite what the effect, purpose, or outcome is supposed to be. In fact, not even those in charge really know what to expect, whether it will work, or, come to that, how to make it work. This could well be a messy situation, but, in Oppenheim’s eyes, such uncertainty would have been quite wonderful, since, for him, machines, which he saw as a metaphor for the artist and for his thinking, were perfectly liable to have flaws and to break down.

Launching Structure #3, my personal favourite, consists of myriad glass tubes, reminiscent of a chemistry laboratory, and various motors whirring and purring at different speeds. Some of the tubes are loaded with fireworks, others remain empty. Again, how this will work when turned on indoors, I cannot predict, and I’m tempted to make the trip back up to Leeds to find out. It is all one big experiment, and, just as in the lab at school, something, somewhere is bound to go bang. The machine will be being put into action at 2pm daily, and, it is to be assumed, will somehow adhere to health and safety regulations, which surely would not permit the launching of fiery missiles within a confined space full of onlookers. In fact, this enormous and preposterous creation is only a prototype for a version 10 times larger, created and employed (outdoors) in Geneva – and no, not at Cern, although surely there is some overlap between the mindset of this seemingly nutty artist-cum-inventor and that of the respectably authorised scientist? Each creates something mind-boggling for the average person. Furthering his metaphor of machine as artist, Oppenheim’s flares and fireworks – shooting out at all angles and at heady speeds – stand in for ideas. This analogy perhaps gives us an insight into the unpredictability and mayhem inside the head of such a creative personality, whose thoughts are always the brightest of sparks.

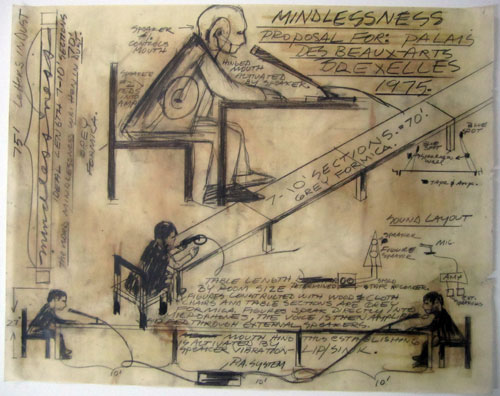

The drawings on the walls, which detail every nut and bolt and twist and turn of the contraptions on display, look, to all intents and purposes, like explicit instructions for assembling them – something that might have been helpful, since the two machines were brought over from New York to Leeds, where Oppenheim’s widow, Amy, helped to install them. In fact, the drawings were done after the machines had first been built, detailing their errors and acting less as a document of actuality and more as one of an unrealised utopian idea.

Even without these machines in action, the galleries reverberate with whirring and thumping, sounds of mechanical processes. The film room, separated by just a curtain, has a loop of four works on show, the longest of which, Echo (1973), consists of the sound of Oppenheim slapping a wall with his hand – a repetitive and constant thud, nothing startling, nothing exciting, nothing interesting, one might say, except for the fact that one is instantly intrigued as to why he might have done this (good question) and how long it might go on for (half an hour, but I defy anyone to sit through the full length). Over the top of this, Oppenheim’s voice resounds across the rooms in the sound-sculpture Ratta-callity (1974), a piece in which he calls for the recognition of radicality as an attitude.

Whether Oppenheim’s work really is, or ever was, an example of the radical, I’m not convinced. His machines – and drawings, come to that – for me, conjure up the visions of a true radical, Leonardo da Vinci. Nevertheless, Oppenheim’s crazy ideas and mad-hatter constructions certainly made me chortle out loud and set my own cogs turning as to how they might function. To really enjoy this exhibition, you need to unleash your imagination and allow it to wander as wildly as the artist’s – you need to let your mind become a metaphorical machine generating fireworks, sparks and flares.

The exhibition is complemented by two concurrent exhibitions within the Institute, Stephen Cripps: Pyrotechnic Sculptor (21 November 2013 – 16 February 2014) and Jean Tinguely: “Spiral” (1965) (25 September 2013 – 5 January 2014).

Dennis Oppenheim’s installation “Trees: From Alternative Landscape Components” (2006), investigating relationships between natural and manmade environments, is also currently on display at the nearby Yorkshire Sculpture Park.

![Dennis Oppenheim. Kunst als Lebenritual [Art as Living Ritual]. Firework display in a park in Graz, Monday 7 October 1974, 19.30. A photograph of the fireworks sign was shown in the gallery with the remaining wood construction. © Dennis Oppenheim, photograph courtesy Dennis Oppenheim studio.](/images/articles/o/oppenheim-dennis-2013/ArtAsLivingRitual.jpg)