New Museum, New York

7 May – 29 June 2014

by ANNE BLOOD

Titled Is It Possible to be a Revolutionary and Like Flowers? (2012-14), it is the first work in Henrot’s current exhibition at the New Museum, which includes several videos and works on paper that variously explore how visual systems structure the way we understand (or perhaps try to understand) our world. As a whole Is It Possible to be a Revolutionary and Like Flowers? presents itself as a formal opposite to Grosse Fatigue, whose driving beat seems to propel an almost insatiable quest for knowledge; instead, the installation is quiet and much more uniquely personal as a translation of the books from the artist’s library into ikebana floral arrangements. Beginning with such an introspective work is interesting. It is arguably an overly subjective way to start a solo exhibition, one that too immediately gives away the artist’s prejudices and interests as gleaned from the titles in her library. A label giving the name of the book, its author, and a short quote, and identifying all the plants used accompanies each ikebana arrangement. The quotes are pithy and often funny, but few famous lines appear, leaving one to wonder if the sections have particular relevance to Henrot. Or, perhaps, she is playing with our desire to construct an impression of her psyche from such a deceptively inconclusive amalgamation of data.

[image2]

Examining a collection to find new meanings or inspiration is often a central part of an artist’s residency at a museum. The host institution hopes that the visiting artist will enliven its collection by finding fresh ways to connect history to the present. Created as part of her residency at the Smithsonian Institute in Washington DC, Henrot’s video Grosse Fatigue combines footage of the holdings of the Smithsonian with active internet browser search windows, investigating both how we archive and look for information. The setting for the video is the artist’s computer desktop and the action begins after the phrase “history of the universe” is typed into a search engine and a deep voice says: “In the beginning there was no earth, no water – nothing.” Variations of this line are found in the introduction to many creation stories across cultures, a fact emphasised as Henrot weaves together fragments of these tales with snippets of scientific information into a long poem delivered in the style of spoken word. In Grosse Fatigue, images and text are rhythmically stitched together and unexpected connections are made between disparate subjects: a rocket blasting off into space is followed by a picture of Justin Bieber’s abandoned pet monkey, a link both bizarre and oddly logical if one tries to think like a computer, joining key terms such as “space travel” and “monkey”. As the film progresses the succession of ideas becomes an excess of information and the effort to gather information in order to construct a more complete picture is revealed to be a Sisyphean task.

[image3]

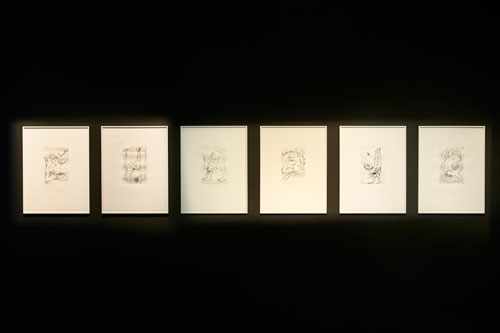

The connection between seemingly disparate sources is also the premise of a series of etchings titled Légendes Dorées (Golden Legends) (2010), which depicts the martyrdom of a number of Christian saints in poses that simultaneously evoke a catalogue of yoga positions. At once ridiculous and hilarious, the series is not meant to criticise religion or spirituality, but through these humorous juxtapositions to draw out the shared affinity between a martyr’s sacrifice and subsequent canonisation and the promise of transcendence through self-discipline in yoga. The work also points to the transformation of traditional spiritual practices to suit our contemporary, largely secular, consumerist society.

In the 35mm film Coupé/Décale (2010), shot on the Pacific island of Pentecost in the Vanuatu archipelago, Henrot addresses the appropriation of “exotic” rituals. The film centres on the demonstration of a rope-jumping ritual traditionally performed by tribesmen living on Pentecost to signal the passage from youth to adulthood. This ritual is also the precursor of recreational bungee jumping – ironically now seen by many as a means to reconnect with the daredevil spirit of youth. While filming, Henrot took the position of both researcher and voyeur, capturing a ritual that is now performed for a visiting audience seeking to experience an “exotic” culture. An anthropologist’s impulse drives much of Henrot’s work; however, in videos such as this, experimental film-making and editing are equally important. While editing, Henrot cut the 35mm filmstrip in two, creating a mark that tarnishes the perfection of her document. Both sides of the cut film depict roughly the same image, but they are forced just marginally out of sync, running continuously, but one second apart, making us more aware that what we are watching is already a translated ritual.

[image4]

Disorientation often arises in Henrot’s work as objects and ideas are displaced from their original source and reprocessed. In an interview with art curator Cecilia Alemani from 2012, Henrot discusses what she sees as a form of over-communication, or even over-saturation, of information in our own effort to construct a globalised worldview. But even if such processes are by their very nature doomed to fail, Henrot still feels compelled to participate rather than simply critique. Is It Possible to be a Revolutionary and Like Flowers? is the most obviously self-reflexive work, but Henrot never takes the position of a passive observer: her own subjectivity and authorship are always present, as were are playfully reminded in the scattering of snapshots of the artist stealing flowers from window boxes on the Upper East Side to make Jewels from the Personal Collection of Princess Salimah Aga Khan (2011–12).

[image5] [image6]